It’s been nearly a year now since I started Freud’s Butcher, and what a roller coaster ride it’s been! I’ll talk more about that in August, the actual one-year blogiversary. It’s just a fortuitous coincidence that these last few weeks have made me re-examine one of the blog’s basic premises, while reminding me why I started writing here.

My Mother’s Story — and She Stuck to It

One of the few family stories that I recall from my mother is that her cousin Stella Schmerling had been sent to see Dr. Freud in the hope that her limp would prove to be psychosomatic. It was such a striking story, in fact, that I made it a centerpiece of my ruminations about my family history.

I wrote on the Psychology page:

Stella had a limp of unknown origin, one that didn’t respond to physical treatment. Hoping that the condition was psychosomatic, Stella’s parents decided to seek out the talking cure for their daughter as a last resort.

This tale always led me to assume that Freud was considered a kind of faith healer in Vienna, only without the religious faith. But now that I’ve looked into the matter a bit, that doesn’t seem very likely.

I have no reason to doubt my mother’s story, although I know for a fact that Freud didn’t cure cousin Stella’s limp. When I met Stella in Vienna, decades later, she still had a draggy leg.

This raises several questions: Why would Freud have agreed to see Stella? Surely not because she was the niece of his butcher. Did he have other ties to my mother’s family? Was Stella’s father, David Schmerling, a member of the same B’nai B’rith lodge where Freud presented many of his seminal papers on the workings of the mind because Austrian anti-Semitism kept him from university podiums?

Banishing the B’nai B’rith Theory

In the last year, I’ve learned a few things.

The first was that the Vienna lodge of B’nai B’rith would not have had let my great uncle David Schmerling, a jeweler and therefore a mere tradesman, into the Vienna lodge. As I detailed in Five Genealogy Lessons I Learned from B’nai B’rith (Once I Stopped Sulking):

… the members of all the Austrian lodges, from their inception, when Austria was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, were members of an elite and educated class. Mostly physicians, members included lawyers, architects, writers and playwrights, lawyers, academics, and even a few artists and interior designers. All European lodges had these standards for membership.

So I scratched the B’nai B’rith membership theory.

Sometimes an Illness Is Just an Illness

In the mad flurry of correspondence I’ve been having with the Schmerling family since I made contact with them, and especially with Stella’s niece, Rita, one fact about Stella emerged: She had polio when she was a child.

That’s pretty straightforward.

Stella’s sister, Hermine (Herma) Schmerling is 95 and in a home in London. She has Alzheimer’s, but on good days, her daughter Rita is able to glean some memories from her. Herma has no recollection of Stella being sent to see Freud, though she recalled — correctly — that the butcher shop in Freud’s building was not kosher, contrary to the Freud Museum’s designation.

I think it’s time to put the Stella-was-sent-to-see-Freud theory to rest. Did I imagine my mother said it? Was she misremembering — or spinning a good story?

Does it really matter?

Close Encounters With Freud

Over the past year, I’ve found several points of Kornmehl family intersection with Freud, mostly where you’d expect it: At the University of Vienna Medical School. There’s documentation that Viktor Kornmehl went to visit Freud on his 75th birthday as the Chairman of the Academic Association of Jewish Medical Students. And 90-year-old Ludwig Kornel recalls that his father, Ezriel Kornmehl (who changed his name to Ezriel Kornel) transferred from medical school in Poland in order to study with Freud in Vienna.

A story that’s a bit more unexpected: Curtis Allina — nephew of the Other Siegmund Kornmehl, and the man who put the heads on Pez — lived across the street from Freud when he was a young boy. In his Shoah testimony, he recalls peering through his window into the psychoanalyst’s office and watching him listen to patients and smoke cigars.

Viktor and Ezriel weren’t very closely related to my family; Curt was, through Anna Kornmehl’s marriage to Curt’s uncle Siegmund Kornmehl — the brother-in-law of the Siegmund Kornmehl who ran the butcher shop in Freud’s building (is your head spinning yet?). But I don’t doubt that 19 Berggasse was a hub not only for Freud’s devotees but also for those who stopped by to say hello to the Kornmehl relatives working in the ground-floor butcher shop.

Back to the Schmerling Family

Those who might have been found in the shop include Marie/Mitzi Schmerling, according to her granddaughter, Rita, who wrote: “My grandmother worked in the family butcher, apparently because they needed the money. She was also able to bring home meat which they gladly accepted.”

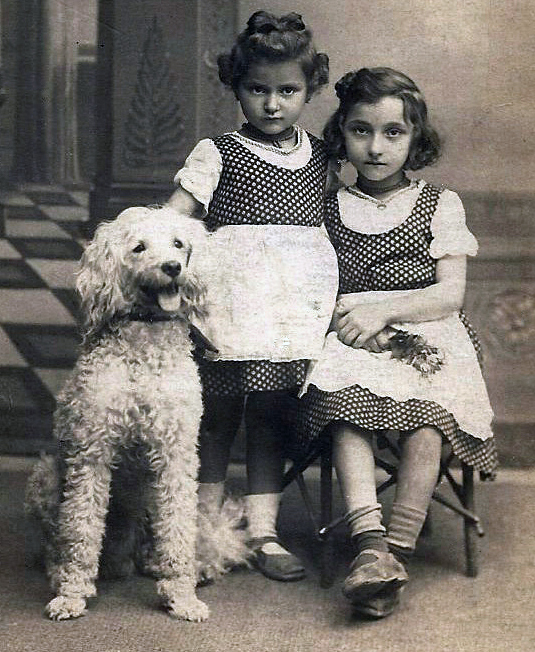

Rita also wrote, in her initial note to me after looking at my blog: “The first photo I saw and instantly recognised without reading any names was of Stella nee Schmerling. That was my darling Auntie Stelly, my mother’s older sister.”

And from a later email:

Auntie Stelly was the best…. My Omi [grandmother Mitzi Schmerling] taught me lots of cooking skills and Aunty Stelly also loved to cook and had done a patisserie course before the war. She… taught me how to make amazing cakes, home-made apple strudel and all kinds of stuff I avoid making nowadays – but I enjoyed all that for many years, especially when my children were young.

As I’ve mentioned, I met both Stella and Mitzi Schmerling once, in Vienna, and wasn’t able to speak with them because they spoke no English and I spoke no German. But now, through their niece and granddaughter, I am getting to know them and other members of the Schmerling family. So as much as Freud is a nice hook, both to interest others and for the historical context/documentation of the era that he provides, the primary goal of my research is to get to know my mother’s family. It doesn’t really matter if Stella saw Freud. What’s important is that I know a great deal more about her — including that the consultation was almost certainly a figment of my mother’s imagination. Or mine.

I’m not sure why either of us would make that up. What say you, Dr. Freud?

On Jul 20, 2013, at 11:10 AM, David B Crawford wrote:

If Stella was sent to consult with Dr Freud, also a well known neurologist, it would not be to “cure” her infant paralysis (polio) but to help her better cope with her disability, psychologically. Given his expertise in neurology, he no doubt was was consulted on cases where “hysteria” either caused or complicated medical problems. It is well to remember that both conditions can and do exist in the same individual; they are not mutually exclusive. Freud, who knew this better than anyone of his day, had been an attentive student of the great neurologist. Charcot at the Salpetriere in Paris. It was there where Charcot demonstrated both kinds of seizure disorders; those caused by known neurological damage and those that were of “hysterical” (the term used then) or psychological origins. This was long before Freud discovered psychoanalysis to pay his bills.

Therefore, it is readily comprehendable how a lay person would misunderstand that someone with “infant paralysis” was sent to a neurologist sub-specializing in psychological medicine for a “cure”.

You are probably also being confused by the very different connotations for the word Kur in German. That would be a “time out” where you go to rehabilitate after a serious illness. Such was the case for the protagonist who went to a Swiss TB sanatorium in Thomas Mann’s novel “Magic Mountain”.

Hopefully, this makes Stella’s history more understandable. So, yes, it makes a lot of sense that she would consult with Dr Sigmund Freud whether she actually did so or not.

David Benn Crawford, MD

Sent from my iPhone

Thanks for the interesting feedback. This definitely puts a different spin on the idea of a consult, though I don’t know whether my Viennese relatives would have been aware of this distinction; they were tradespeople, as well as laypeople. I know about Charcot, etc. because I know Freud’s history, but I have not been able to find out what your ordinary Viennese person would have understood about Freud’s practice; many of his patients came from abroad.

I’m not sure what you mean about my being confused by the connotations of the word “Kur” in German. My family knew German but I don’t. I read the Magic Mountain back in the day but definitely not in the original.

There is still no evidence that Stella consulted with Freud — either recollections from her family or documentation from the records at either Freud Museum — but it’s good to know why I can’t rule it out on a medical basis.

https://www.google.com/search?client=safari&hl=en&q=image+of+freud+charcot&spell=1&sa=X&ei=bd_qUfeTHZCvigKwh4CADQ&ved=0CCoQBSgA&biw=320&bih=356#biv=i%7C8%3Bd%7C6AgqPot7a7Aj_M%3A

And how interesting to find that no matter how many facts we pile up, the family stories still may conflict with fact–and with each other. My brother and I frequently remember the same event in totally different ways. Some very big things that should be obvious one way or the other–and we’re both very sure that we are right. Tricky thing, memory. And history.

Yes, indeed! I am thinking of scrapping the family history and writing a book about family memories — why they are so elusive and contradictory… I was horrified by how little I recalled about my family — and heartened to realize I was far from the only one.

Irrespective of factual precision, the Stella/Freud tale provides the sort of texture that makes the genealogical trail worth following, at least by this outsider. Every family has lore, and those stories, whether real, speculative, or embroidered, provide interest and insight.

But far more importantly: the photo IS adorable, I was pleased to see it again today, and I think you should sneak it in on even the slimmest of pretexts!

Thank you, Clare. And I’m glad you agree on a key issue: The importance of sneaking the picture of Flooki and the children in whenever possible!

One thing is pretty clear, Freud lived in the neighborhood where the Kornmehl family lived and/or worked. They were sure to have come into contact with him one way or another.

Dr. Crawford comes up with a great hypothesis of why Stella met Dr. Freud. Perhaps your mother knew something about Stella that the siblings did not?

It is also apparent that food played a large role in the Kornmehl family history — either as good cooks, cafe owners or butchers…

Yes, indeed — the interactions of Freud with the Kornmehl family are undisputed; you don’t have a butcher shop in the same building as someone for 44 years without some kind of relationship being established. It’s just the extent and the nature of that relationship that remains mysterious.

I think the crux of the matter remains something I am going to double my efforts to pursue: What did Viennese laypeople know about Freud — including those who lived and worked in his neighborhood? Would Freud’s complementary neurological practice have been popular knowledge? That’s not why his famous patients went to see him. The Doktors Kornmehl might have been aware of the issues, but the rest of the family? I suspect then, as now, Freud’s ideas were distilled into the lowest common denominator. After all, his books were burned in Germany for his fixation on sex, not neurology!

But that’s all theoretical — whereas the family’s involvement with food (including mine, as a food writer) is undisputed!

Nice piece. Coming back to the same theme – getting to know family!

Thanks, Elaine. Yes — it’s a fascinating process!