May 6, 1931, was Sigmund Freud’s 75th birthday. He was hoping to avoid a fuss, especially since he had been in the hospital since late April, undergoing a painful operation on his jaw, and had only returned home to 19 Berggasse the previous day.

Freud Feted

No such luck. According to biographer Peter Gay (Freud: A Life for Our Time, pp. 574-5):

[Freud] could veto festivities but not stop an avalanche of letters from friends and strangers, psychoanalysts and psychiatrists and admiring literati. Telegrams poured in from organizations and dignitaries, and Berggasse 19 was awash with flowers.

Among the well-wishers were Albert Einstein, the Mayor of Frankfurt, the chief rabbi of Vienna and the organizers of a banquet in New York attended by Theodore Dreiser and Clarence Darrow.

The 22-year-old Viktor Kornmehl, who had just completed medical school and was the Chairman of the Academic Association of Jewish Medical Students, marked the occasion by attempting a personal visit:

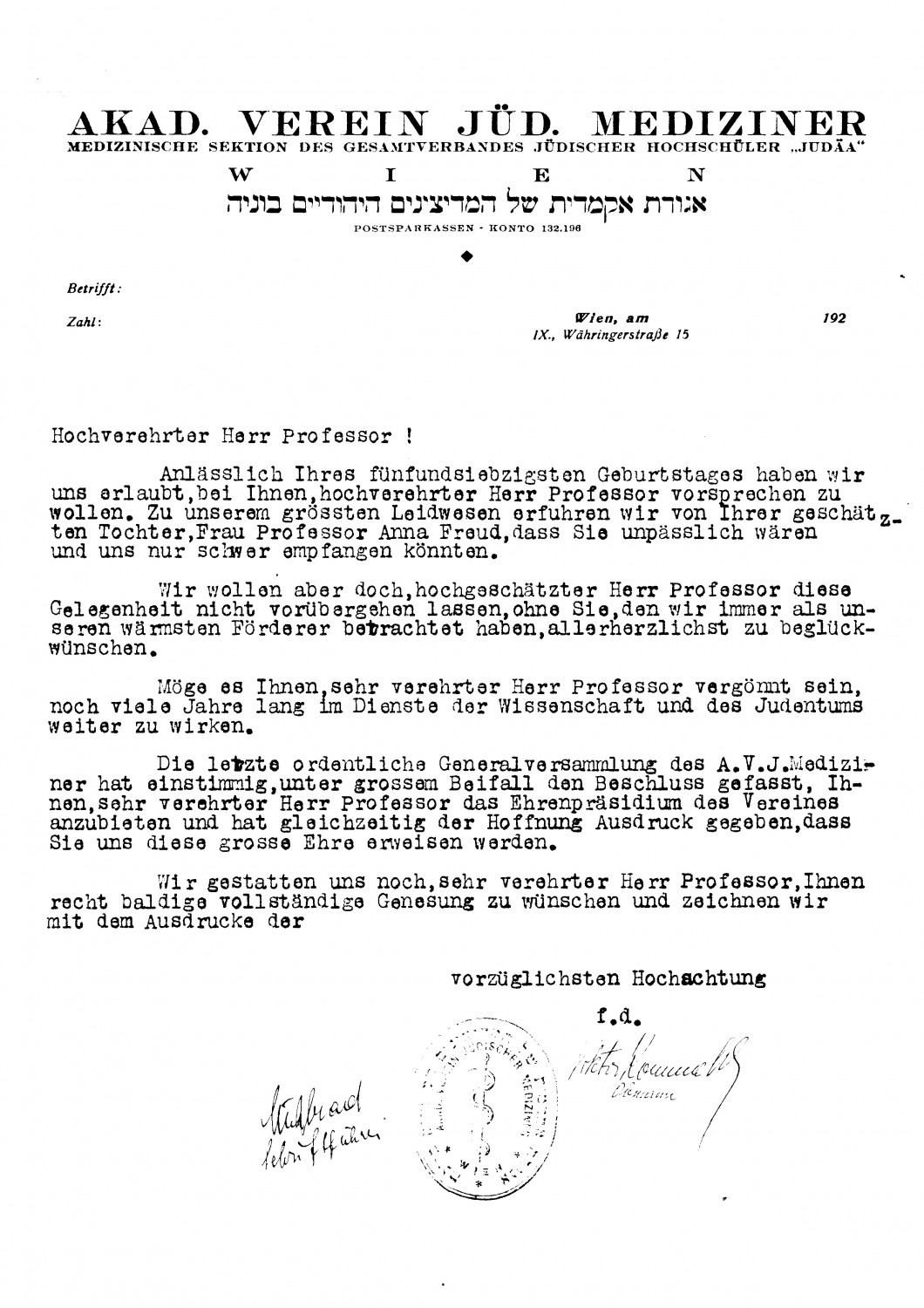

The letter reads in English:

Acad. Assoc. of Jewish Medical Students

Medical Section of the General League of Jewish University Students “Judaa”

Vienna

Vienna, IX, Waehringerstrasse 15

Esteemed Professor,

On the occasion of your 75th birthday we allowed ourselves the liberty of calling on you, esteemed Professor. To our great regret, we were informed by your revered daughter, Professor Anna Freud, that you were indisposed and hardly in a position to receive us.

Nonetheless, revered Professor, we cannot allow this occasion to pass without sending our most heartfelt wishes to one we have always regarded as our most stalwart supporter.

May you be granted many more years, most esteemed Professor, to continue your activities in the service of science and the Jewish people.

The last regular general assembly of the Acad. Assoc. of Jewish Medical Students unanimously and with enthusiastic acclamation resolved to offer you, esteemed Professor, an honorary seat on our Board of Directors and at the same time lent expression to the hope that you would accord us the great honor of accepting.

Finally, esteemed Professor, we would like to wish you a very swift and complete recovery and express to you our very highest regard,

(signed) Victor Kornmehl

Chairman

How Freud Might Have Reacted to Viktor’s Letter

According to Gay, “Freud took some of these tributes coolly, even resentfully. When he learned in March that to celebrate his seventy-fifth birthday the Society of Physicians proposed to make him an honorary member, he bitterly recalled the humiliations the Viennese medical establishment had visited on him decades before. In the privacy of a letter to [Max] Eitingon, he called the nomination repellent, a cowardly reaction to his recent successes.”

But Erika Weinzierl, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Vienna, puts things into a different context. In a paper titled, “The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries” (2003), she explains that:

Although 11 percent of Jews marrying between 1870 and 1910 already were jurists, doctors and journalists, their numbers did not really begin to rise significantly before the twentieth century. In the public sector, there was not yet a single Jewish civil servant in 1880, but by 1910 already 4 percent of those marrying belonged to this category. Among them, the highest ranking were university professors, while the majority held positions in the postal or railroad services; Jews did not have access to ministerial level positions.

The situation was different with the university professors in the Medical Faculty, and it is here that Jews made some of the earliest advances to full or nearly full equality and recognition, even if they encountered more difficulties than their non-Jewish colleagues. Sigmund Freud, for instance, became Privatdozent [docent] for neuropathology in 1885, in 1890 the Medical Faculty asked the Ministry of Education to appoint him tit. außerordentlicher Professor [a type of honorary professorship], and in 1902 he finally received this title. However, he himself never sought this appointment from the faculty.

Weinzierl is suggesting that, in the general scheme of things, Freud didn’t do too badly for a Jew. Perhaps his resentments against a rebuff that wasn’t much of a rebuff for its era grew proportionately with his success.

In any case, Freud certainly would have been sympathetic to the Jewish medical students who, in the early 1930s, were themselves being subjected to a growing tide of antisemitism; I’ve described two incidents that took place in May and October of the following year, 1932, in recent posts. In one of those posts, Dr. Kornmehl, Prof. Freud, and Jewish Activism, I discussed how Freud, nonreligious though he was, would likely have admired young Viktor Kornmehl’s Jewish activist zeal.

In his letter, Viktor calls Freud “one we have always regarded as our most stalwart supporter.” It is difficult to know how literally to take this. Many organizations claimed Freud as a supporter. I can find no record of Freud’s involvement with the Academic Association of Jewish Medical Students. Nor have I located Freud’s response to the group’s offer of an honorary seat on the Board of Directors but, since I don’t imagine it involved attending any meetings, he would have had no reason to refuse.

How Viktor Might Have Reacted to the Realization that Freud Had Many Well Wishers

When Viktor realized that Freud had just gotten out of the hospital and that half the world had turned up at his doorstep — though most only metaphorically — he might have felt both vindicated that he wasn’t allowed access and a tad embarrassed. Or maybe not. Viktor seems like a confident young man. Although the letter is very deferential, as befits an address to an older public figure, he might have believed he had enough in common with Freud as a fellow Jewish doctor to assume he would not have been imposing on his time.

One thing I feel more comfortable speculating about is what Viktor would have done when he was turned away by Anna from Freud’s door. He surely would have gone downstairs to the butcher shop at 19 Berggasse to say hello to its owner, his cousin Siegmund Kornmehl who, as I discussed in The Whole Megillah: A Purim Mystery, must have had a close relationship with Viktor’s father.

A word about the image, the letter, and the translation

The image next to the title of this post, from Wikimedia Commons, is of 101A. Schlossergasse 117, Freiburg, the birthplace of Sigmund Freud in Pribor (now in the Czech Republic). For Freud’s 75th birthday, the street was renamed Freudova.

The letter appears here with the kind permission of the Sigmund Freud Museum London, where it resides in the archive.

The translation has an impressive lineage. The first English version was provided by Viktor’s son, Hillel. I asked my friend (and frequent contributor to this blog) Lydia Davis to take a look at it. She carefully crafted a new version. Lydia is comfortable with German but is better known for her French translations of Proust and Flaubert. She, in turn, asked her friend Susan Bernofsky, who is the translator of Robert Walser, among other German-language authors, and is presently Chair of the PEN Translation Committee, to check her draft. The final revision you see here is Susan Bernofsky’s.

Viktor Kornmehl might not be as famous as Sigmund Freud but his correspondence has nevertheless received the close attention of two of the world’s top translators.

This is day 25 of the Family History Writing Challenge. I’m feeling very proud of my kin.

Would Viktor then also have been able to have a sandwich at the butcher shop?

The shocking revelations of your previous posts about the vicious attacks on Jewish students and professors at the university causing even hospitalizations, must have been disheartening to all.

It really added so much in order to fully appreciate the context of the times in which this letter was written. And these top translators taking pains to review the exact wording helps to convey to this reader Viktor’s anxious desire to feel more fully Freud’s support in future. Seems his request was left unanswered, but why really is not so clear.

Good question, Diane. I’m still trying to get a handle on butcher shops of the day. I think he would have been able to get cold cuts for a nice nosh, but not the bread.

I didn’t feel any anxiety in the letter, just lively interest. I’m pretty sure that Freud did answer, but the letter is not archived.

I dont detect it in the letter either but reading between the lines, though maybe I’m not paying attention to the chronology, Wouldn’t they be feeling the effects of those attacks and be looking for his validation and some sense of protection there?

Yeah, I realize it’s confusing — I’ve been skipping back and forth — but the attacks took place afterwards. And Freud was so busy with other issues that he would not have been involved, even if he was sympathetic, and he wouldn’t have provided much protection. The Nazis burned Freud’s books in Germany in 1933.