Sigmund Freud and Me

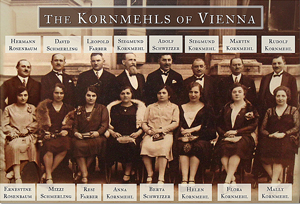

Some facts about my mother’s family and its ties to Sigmund Freud are indisputable. There’s no question that my great uncle, Siegmund Kornmehl, had a butcher shop downstairs from Freud’s home and offices at 19 Berggasse in Vienna and that he sold meat to Freud’s wife.

Some facts about my mother’s family and its ties to Sigmund Freud are indisputable. There’s no question that my great uncle, Siegmund Kornmehl, had a butcher shop downstairs from Freud’s home and offices at 19 Berggasse in Vienna and that he sold meat to Freud’s wife.

Other facets of the family relationship to the father of psychoanalysis are a little less clear cut, but I came to learn that meat was not the sole connection. As time went on, I realized that I was becoming a little possessive about Freud and protective of his reputation. You don’t have to be in analysis — or know anything about transference — to figure out that he came to represent another Viennese Jewish man, my father, who was also forced to flee the city.

Vienna Did Not ♥ Freud

According to an excellent essay by Lilian Furst, “Freud and Vienna”:

Throughout his life Freud enjoyed a far higher reputation beyond Vienna than in his adopted hometown. Most members of his circle came to him from elsewhere… Viennese adherents to psychoanalysis were decidedly in the minority.

And as Freud’s biographer Peter Gay put it in his introduction to Berggasse 19: Sigmund Freud’s Home and Offices, Vienna, 1938: The Photographs of Edmund Engelman:

Guidebooks and leaflets advertising the city barely mention Freud’s name. The public indifference, the latent hostility, are chilling…. Vienna, it seems, has largely repressed Freud.

A Freudian Nonslip

My mother’s knowledge of Freud — or at least her interpretation of his ideas — became particularly relevant to me in the late 1970s, when I joined a therapy group designed to deal with the impact of the Holocaust on the next generation. The group later became the basis of the book Children of the Holocaust: conversations with sons and daughters of survivors by Helen Epstein. To paraphrase my mother’s reaction to the news that I was getting involved with psychotherapy: “So you’re going to talk about me and tell everyone how everything that’s wrong with you is all my fault?”

As it happens, nothing could have been further from the truth. It was as a result of the group that I stopped blaming my mother for everything that was wrong with me. I gained a profound sympathy — and respect — for the timorous young woman who was forced to leave her parents and the only home she knew and flee to a strange country, alone, almost broke, barely knowing the language. Yes, my mother was overprotective and, often, critical. But she did the best she could and, given her circumstances, that best was pretty damned good.

Learn more about Genealogy

Leave a Reply