This seems to be Revisionist Week.

Monday I wrote about how my great uncle’s kosher butcher shop in Freud’s building was not kosher after all: The Butcher Shop in Freud’s Building: Kosher or No?

Yesterday I followed up a post about wanting villainous ancestors with one that said that it might not be such a good idea if those ancestors were in your recent past: “Inheritance”: Revisiting the Victim vs. Villain Debate.

Today I’m going to have to revise a post I wrote about Freud’s metaphorical finger to the Gestapo upon departing Vienna.

Freud’s Defiance

In the post titled Freud to Gestapo: Drop Dead, I discussed the controversy surrounding the fact that, before he was permitted to leave Austria, the SS insisted Freud sign a statement verifying that he had not been mistreated.

In the post titled Freud to Gestapo: Drop Dead, I discussed the controversy surrounding the fact that, before he was permitted to leave Austria, the SS insisted Freud sign a statement verifying that he had not been mistreated.

According to the 1989 biography by Peter Gay, Freud: A Life For Our Time, the 82-year-old Freud wrote: “I can most highly recommend the Gestapo to everyone” (Ich kann die Gestapo jedermann auf das beste empfehlen).

Gay questioned his subject’s psychological motives for taking such a deadly risk, hypothesizing that Freud may not have wanted to leave Vienna after all. A Time magazine reviewer of Gay’s biography agreed that this behavior was very risky, but attributed Freud’s behavior to the fact that he was a control freak.

I argued that Freud’s comment wasn’t all that risky and that his motives didn’t matter: His defiance was inspirational.

Too bad the incident never happened.

Is Lying to Your Son Kosher?

At the very end of a lecture on “Freud and the Language of Humor” given at a British psychological conference in 2002, Professor Michael Billig drops a bombshell:

At almost the last moment, Freud managed to obtain the paperwork to leave Vienna for England. As a final step, he had to sign a form saying that he had not been mistreated by the Nazis. He told his son that he had added the words ‘I can thoroughly recommend the Gestapo’. It seemed one last act of rebellion. The document has surfaced recently, and it appears that Freud never wrote the words (Ferris, 1997).

The Billig citation refers to Paul Ferris’s 1997 biography, Dr Freud: A Life.

Apparently the Ferris biography was not very kind to Freud. Billig doesn’t talk about the book, other than to cite it (in the paper that I linked to) as the source for the information about the Gestapo joke. Billig, unlike Ferris, is a fan of Freud, and excuses him for a little duplicity:

Even the Gestapo would have understood his irony. The joke might literally have been the death of his wife and children. As it was, four of his sisters failed to escape. The joke could not be spoken, or written. But it could be thought. Thinking a joke is not enough, for joking needs to be a social act. So Freud told the joke to his son, pretending that it had already been made. As such, the joke contained an element of deceit. Such is the strangeness of humour that this element of deceit does not diminish the essential morality of the joke. Nor does it detract from the greatness of its creator.

The Importance of Primary Sources

Which brings me to primary sources.

Am I going to beat myself up for missing this important information about the Gestapo incident? Of course not, though self-flagellation is one of my favorite activities. I found it at the very end of an obscure 2002 pdf that I happened to be reading because I’m interested in the topic of Freud and humor. I — and others who discussed the incident, even after the Ferris biography came out — relied for our information on a 810-page (including index and footnotes) biography of Freud that’s considered definitive.

Nor am I going to critique Peter Gay, who read through hundreds of Freud’s letters — including, I assume, the one that Freud wrote to his son about the Gestapo incident (though Billig uses the word “told” so maybe  it is a transcribed conversation). I looked through the all footnotes for that chapter in Gay’s book and couldn’t find a specific reference for it.

it is a transcribed conversation). I looked through the all footnotes for that chapter in Gay’s book and couldn’t find a specific reference for it.

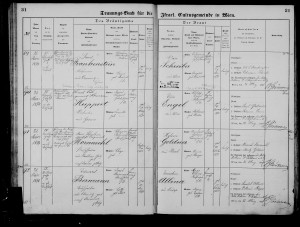

I’ll just give kudos to Paul Ferris, who bothered to go to the source, presumably the Austrian exit documents (but no, I am not going to track down the Ferris biography to check. So sue me).

The reference in the Freud Museum materials to the kosher butcher shop that wasn’t kosher that I discussed earlier this week is a little more difficult to understand. There was clear documentation in ads of the time that the butcher shop in Freud’s building wasn’t the one of the three Siegmund Kornmehl butcher shops that the observant would have gone to. Nor does the blow up of the Edmund Engleman photo of the butcher shop used by the Freud Museum as a showcase for its transformation into an art gallery show give any indication that the shop was kosher.

But never mind. Siegmund Kornmehl’s kosher butcher shop was just down the block from Freud’s home, so it would have been convenient to Frau Freud. Most of all, the reference to a kosher butcher shop on the Freud Museum site was what spurred me into researching my family’s history, inspiring the “aha” moment when I realized that my mother’s story about Freud getting kosher meat from one of her uncles must be true.

All that said, every genealogy resource I read talks about the importance of going back to primary sources. So I herewith promise to rely on primary sources whenever possible — and to correct my mistakes whenever I find them.

I imagine genealogy is a bit of a circular process – it must be an interesting new experience for a writer as meticulous as yourself. Don’t be afraid to write about what you find, even if you might have to correct it later. The circuitous journey is more interesting for your readers than if we were only to get the straight line between A and B.

Thanks for saying I’m “meticulous,” Amy! I’ve been feeling like a bit of a research slob. Refining information is probably necessary in most research projects but blogging about your findings means you have to do the refining in public if you’re as guilt ridden as I am. Of course, there’s a little “neener neener” aspect here too since I get to correct statements made by venerable sources like the Freud biography and the Freud Museum 😉

You have my sympathy. We had to straddle lots of erroneous information when writing our biography of Quincy Tahoma, the Navajo artist. Early on we found that secondary sources were wrong, wrong, and wrong. Since primary written sources were hard to find, we had to rely on oral history interviews we did. But of course human memory is definitely faulty. So, there you have it. History is what we say it is.

It’s an endlessly fascinating process — if it wasn’t also frustrating! But of course, in the end, you wrote a wonderful definitive biography of Quincy Tahoma. And there’s a lesson about perseverance in that too.

Nice post– And primary sources are usually more exciting, too. Even if others have visited them before you, you’ll have your own particular take on what you find, and also that feeling that you’re “alone” with a document that has its own valuable history. And I’ll second Amy, that it’s more interesting for us to watch you travel the circuitous path and experience your discoveries (and corrections) along with you than merely to be handed the end results.

I also agree with Vera about the unreliability of people’s memories. And even official documents can be unreliable. But that’s what makes it all such an adventure.

Thanks, Lydia. Yes, it’s the journey, not the destination, that’s often more interesting. But it suddenly struck me how odd it was to be changing my perceptions three times this week!

I somehow am reminded of an unintentionally funny line in some ad copy about a treatment for varicose veins that I saw today that read:

“Sessions with Dr White last approximately 30 minutes with little after effects.”

🙂

Edie Jarolim, your exploration of Freud’s alleged defiance to the Gestapo offers a captivating journey into historical revisionism. The importance of primary sources in unraveling the truth is underscored, revealing the nuances of Freud’s actions. The complexity of humor in such a context adds a layer of intrigue.