A few weeks ago I posed the question of whether it’s preferable to have villainous or victimized ancestors. I came down clearly on the side of the villains, based on my own family’s fit into the victim category. Several people commented about dastardly relatives in their distant past, including my friend Clare, who had an Indian hunter on her family tree. My friend Lydia had the best of both worlds — a relative who was burned as a witch. That is, she was considered a villain in her times, but died a victim, making her both interesting and morally pure.

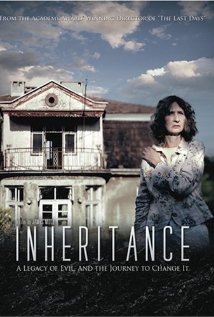

Commenter Anna Redsand suggested that, for another perspective on the issue, I rent the movie “Inheritance,” about a meeting between Amon Goeth’s daughter and one of his surviving victims. So I did. And realized that comparing relatives in the distant past to those more directly affected is comparing apples and oranges — or open wounds to skeletal remains.

A Bit of Background

Amon Goeth was “immortalized,” if I can use that term, by Steven Spielberg in “Schindler’s List.” Played by Ralph Fiennes, Goeth was the volatile Nazi in charge of the Plaszow labor camp where the Jews who worked for Oskar Schindler were sent. According to one article on JewishGen.org:

The camp of Plaszow was originally designed to be a work camp. However, like many other Nazi camps, shortages of food existed, prisoners starved or were worked to death, or summarily shot for no reason. The camp had been opened in December 1942. More than 150,000 civilians were held prisoner in Plaszow….The conditions of life in this camp were made dreadful by the SS commander of the camp Amon Goeth. A prisoner in Plaszow was very lucky if he could survive in this camp more than four weeks.

As we learn in “Inheritance,” Monika Hertwig never knew her father, Amon Goeth. He was hanged in September, 1944; she was born in 1945. Nor, for a long time, did she know anything about the camps. “No one talked about World War II,” she says.” Her mother told Monika that her father “died for his country.”

She began gleaning bits and pieces of the truth, but it wasn’t until “Schindler’s List” came out that she got the full picture. “I hated Steven Spielberg,” she says. But then she became determined to learn more. She saw Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig, who had been one of Goeth’s two house slaves, in a TV documentary and began a campaign to speak to her. “If you can’t change the past, maybe you can change the future,” she says.

The Interaction

The emotional center of the film is the meeting of Helen and her daughter, Vivian, with Monika at the site of the former camp, including the villa where Helen worked and where Goeth watched the Jews go to work, loaded his gun to shoot them at whim — Helen could tell when he was in the mood by the hat he put on — trained his dogs to rip them apart, etc.

Helen has been grappling with her past for a long time, but she has not been back to the camp or the house in Poland. It is, of course, very upsetting for her. But it is Monika who is beside herself, distraught to the point that Helen puts a comforting hand on her arm, though she has said from the start that she can’t allow her any sympathy — nor forgiveness, which Monika doesn’t expect.

There is no “closure” — that bogus concept — for anyone but it is clear that Helen’s suffering is receding with time, in spite of this re-opening of the wound, while Monika’s is only beginning as she hears of her father’s monstrosities first hand. She knows none of what he has done is her fault, but she feels complicit. She says she hoped to learn to live with the truth, but ends up not being able to believe anything any more.

Several Layers of Reaction

I found that I couldn’t feel the same type of sympathy for Monika as I felt for her father’s victims, but at the same time it became clear that I would want my villainous ancestors to be many, many generations removed from me.

The person I most identified with was Helen’s daughter, Vivian. At one point she talks about how people rebuke her, saying, “Vivian, you weren’t in the Holocaust, your parents were in the Holocaust.” She says, “I know that intellectually but at times I can feel the pain that my parents went through.”

We learn that Vivian’s father, who met Helen after they both survived the Holocaust, killed himself in 1980.

How can people think that Vivian wouldn’t be affected? How can Vivian? Easily. I went through many years under the same impression until I took part of a children of survivors therapy group. I touch on it here, but that’s a whole other story — which I will tell one of these days.

In the meantime, while researching this post, I discovered that Amon Goeth was born in Vienna, and lived there at the same time as my mother and her family did. I also learned that Goeth “orchestrated the final ‘liquidation’ of the Krakow ghetto as well as the ghettoes in several provincial towns, including nearby Tarnow.”

Tarnow is the town where my mother’s family, the Kornmehls, all came from. Goeth helped destroy the Jewish cemetery, the synagogue, my ancestral past… So much for not being directly affected by the actions of that bastard.

And so much for thinking I could tell my family’s story in Vienna without discussing the Holocaust, that I could re-create the era before the Anschluss while ignoring the fact that there were Amon Goeths walking the streets along with my grandparents, great aunts and uncles.

Then again, they didn’t know what was in store for them. Who could have imagined such things? And it’s still worth trying to put my blinders back on to look at their lives without the foreshadowing that knowing the future has brought.

This is an amazing post, Edie. We visited Krakow last May. As you probably know, Shindler’s factory is now a museum/memorial–a rather good one. It reminded me of the holocaust memorial museum in Washington, D. C. We didn’t go to Plaszow. We, did, however, spend most of our time in Krakow in the ghetto which has been/ is being restored. My favorite museum was the Galicia Musuem (http://www.en.galiciajewishmuseum.org). If you visit the website you’ll see that’s it’s a museum of photographs the tell the story of Jews in Galicia over centuries. Each photo is accompanied by text which movingly tells you about the subject of the photo and puts it in context of the overarching narrative of the exhibit. I like quiet when I’m trying to take in something like this, but on the day I visited as I was about a third of the way through the exhibit a group comes through. A young woman speaking southern accented English was leading the attentive cluster of young people. After a moment of cursing under my breath at the “noise” something she said caught my attention. She’s in her early 20’s and from Tennessee. She decided after college to come to Krakow–she works for the museum– to rebuild the Jewish community. She said there are many young people like her that are committed to restoring Jewish life in Krakow. I hope so.

Thanks, Deborah. It’s ironic; I spent a good part of my life avoiding this part of my past and now I’m immersed in it. I do want to go to Poland to visit Tarnow. I hadn’t realized how close it was to Krakow. Those museums sound very moving, and it’s heartening to know that young people are devoted to rebuilding the community.

My mother in law, Frances Leder Kornmehl, found herself separated from her entire family after the liquidation of the ghetto in Tarnov. She was one of the few Tarnov survivors shipped to Plaszow.

Her memories of Plaszow were vivid, and Amon Goeth figures large in all of them. Unlike the Schindler’s List Jews, she had no protection and witnessed the depths of madness and cruelty that Amon Goeth exhibited on a daily basis.

Helen has not revealed only her own story, but that of all those that witnessed Goeth’s malicious acts. In sharing Helen’s story with your readers, you have documented the lives of your Kornmehl relatives who no longer have a voice to do so.

You told me that Frances had been in Plaszow; I hadn’t realized that she was shipped there from Tarnov. I’m getting a larger and larger picture of our family’s story, including parts that I hoped not to know.

I’m glad that I’m able to tell more stories here, even if these aren’t the stories that I would prefer to tell — or, that I would prefer never happened. But you can’t change the past, as Monika said. Maybe I can change the future by getting some stories told.

Very compelling post, Edie, and it shows me what a comparative luxury it is to wallow in centuries-old crimes. Your family’s past is still very much present and horrific. Please pursue this so that we all may learn and remember.

Thanks, Clare — I’ll try. It helps that I have you as a friend to jolly me out of the depths that some of this research gets me into.

Thank you, Edie, for going deep to give this very personal review of Inheritance. The difference between having villainous relatives in the distant or recent past was an important distinction. The metaphor of comparing open wounds to skeletal remains is an apt one.

Thanks, Anna. It was a difficult realization but worth coming to. And thanks for recommending that I look into Inheritance in the first place.