Almost everything Sigmund Freud did has been analyzed endlessly — and why wouldn’t the Analyzer-in-Chief be subjected to such scrutiny? But the diverging opinions on Freud’s behavior say as much about the analyzer as they do about analysand.

I was particularly intrigued by the different responses to one incident: Freud’s metaphorical finger to the Gestapo upon his departure from Vienna in 1938. Before he was permitted to leave, the SS insisted he sign a statement verifying that he had not been mistreated.

The 82-year-old Freud wrote: “I can most highly recommend the Gestapo to everyone” (Ich kann die Gestapo jedermann auf das beste empfehlen).

What His Biographer and a Critic Said

In citing Freud’s parting words, Peter Gay, Freud’s biographer, wrote:

It is a curious act inviting some speculation. Freud was lucky the S.S. men reading his commendation did not perceive the heavy sarcasm lurking in it. Nothing would have been more natural than to find his words offensive. Why, then, at the moment of liberation, take such a deadly risk? Was there something at work in Freud making him want to stay, and die, in Vienna? Whatever the deeper reason, his ‘praise’ of the Gestapo was Freud’s last act of defiance on Austrian soil.

— Freud: A Life For Our Time, p. 628 (Anchor Books ed. 1989)

A reviewer of Gay’s book in Time magazine concurs with Gay’s analysis that Freud’s behavior was dicey and adds: “This defiant and, under the circumstances, risky display of contempt was typical of the man who invented psychoanalysis. Throughout his life, Freud sought to maintain control.”

Freud’s Difficult Decision to Depart Vienna

There is no question that Freud delayed his departure from Vienna, hoping beyond hope — and beyond his expressed acknowledgement of the realities of the situation — that the Nazi regime would fall. Even when it was increasingly clear that it would not, and when many of his colleagues were fleeing Austria, a country showing increasing signs of anti-Semitism, he stayed on. He continued to find excuses after the Nazis occupied Austria: He was too old, too frail, and as he told his earliest biographer, psychoanalyst Ernest Jones, “He could not leave his native land; it would be like a soldier deserting his post.”

It was only after his daughter, Anna, was arrested on March 22, 1938 and detained by the Gestapo that Freud agreed to leave — not an easy feat to accomplish at this point, when the Nazis were both confiscating Jewish property and levying exorbitant departure fees.

What Was Freud Thinking?

It’s impossible to know why Freud said what he did to the officers in charge of letting him leave Vienna. But we do know a couple of things.

Freud’s sense of humor was often sarcastic. For example, when his books were publicly burned in Berlin in May 1933, he said:

What progress we are making. (…) In the Middle Ages they would have burnt me; nowadays they are content with burning my books.

And members of the Gestapo were not known for subtlety or nuance. According to an Associated Press report on June 4, 1938, the date Freud left Vienna:

Vienna’s official Nazi organ, the Voelkischer Beobachter, in reporting Dr. Freud’s departure did not mention his name but referred to the Freudian psychoanalytic school as a ‘pornographic Jewish specialty.’

So I wonder: Why would it be “natural” for the Gestapo to pick up on Freud’s sarcasm and to take offense? Freud had good reason not to overestimate the Gestapo’s self-awareness.

And let’s say the guards did understand what Freud was saying. Can you detain someone for sarcasm? Wouldn’t that be admitting that Freud’s statement was patently untrue, that he was mistreated? Moreover, the world’s eyes were on Freud. In addition to Princess Marie Bonaparte, the people who interceded on Freud’s behalf included President Roosevelt and the American ambassador to Paris.

The SS guards would have had to give a plausible reason for not allowing Freud to leave. “He was mocking us” is difficult to prove — not to mention embarrassing.

How risky, then, was Freud’s comment?

And Do Freud’s Motives Matter?

On one level, of course the underlying reasons for Freud’s actions matter. If it wasn’t for Freud, subconscious motivations wouldn’t be an issue for anyone. Peter Gay maintains Freud defied the Gestapo because he wanted to stay in Vienna; the Time magazine critic suggests Freud was a control freak.

But maybe he lost control, in a sense, and acted instinctively. Freud was a dignified man with a contempt for boors — and with a sense of humor. He might have just been behaving in a way that came naturally.

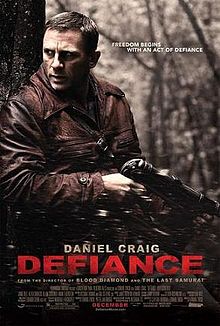

In the end, we won’t know if there was a deeper reason for Freud’s statement. But there are few popular stories of Jews going up against the Nazis during World War II; aside from the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, the only one I can think of is that told in the movie Defiance, based on the actions of the three Bielski brothers. Most heroic tales of the war, from The Diary of Anne Frank to Schindler’s List, focus on righteous gentiles who try to save victimized Jews.

I find the idea of an 82-year old man suffering from jaw cancer using the weapons he had, his intellect and wit, to get the better of the Nazis, very compelling, no matter why he did it.

What do you think?

Update: Sad to report, all speculation is moot because I’ve learned that THIS DID NOT HAPPEN. See Freud, Humor, & the Importance of Primary Sources.

A very thoughtful and provocative column – and now I want to know more about my own conscious and or subconscious motivations that can often be self-sabotaging!

There are surely hundreds of thousands of acts of defiance that have gone on, and gone unrecorded. Meanwhile let us not waste any time in making up for any absence of same.

My last column (see link below) was a direct result of posts by your friends on facebook on your fb page that alerted me, immediately on Sept. 12, to the corrected story about who was behind the Muslim video – and a direct result of my letting them know, was that the Gallup Independent, a small but influential rural paper, ran the AP story correction that next day too.

Well, let’s just call them brave and not worry about the motives.

And I’m glad my Facebook post — and comments by my friends — were helpful. That’s great the the Gallup Independent followed your lead! The print edition of The Week went with the bogus Israel film maker version.

The Week – is that Tucson? btw, time to take another head shot of you I’ll have to swing by –

No, The Week is national — it’s a great publication, kind of a political Cliff’s Notes that summarizes articles from all over the world and from all political perspectives: http://theweek.com/

I’d love a new head shot!

In answer to your question, “What do you think [about an 82-year old cancer sufferer using wit and wisdom against the Nazis]? My first reaction was “delightful”! His sarcasm really was so funny, that I guess I’ll stick with that. Wit and wisdom don’t always have to be received with deep gravitas, do they? Thanks for a great post…you’re turning me into a Freud enthusiast.

And how do you feel about that (i.e., becoming a Freud enthusiast)?

I’m afraid I know more about the theory than I do about the man. I didn’t know about Freud’s penchant for biting sarcasm. It seems to me that in the face of Vienna’s rampant anti-semitism a scathing wit would have been served Freud well. A full frontal attack on Viennese anti-semites much less the Gestapo would have been suicidal. As for my two cents, I think Freud knew exactly what he was doing in his parting sly shot at the Gestapo. I think he knew the Nazi’s all too well. They were a supremely narcissism bunch. Of course Freud surely had ascertained this and as such knew the goons would take his words at face value.

The man is proving to be more fascinating than I had anticipated — I’d always gotten the sense that he was rather humorless and cold. I think you’re right about the Nazis taking Freud’s comments at face value. How could men so sure of themselves imagine a Jew would have the nerve to mock them?

Yes! That too.

This is all fascinating–how Freud is coming to life through the information you’re digging up. As for acts of defiance, I’m thinking of one that occurred in Birkenau: the blowing up of one crematorium by the prisoners who worked there. It took a lot of complex planning, of course, only a few Germans died, the perpetrators were executed. But it was spectacular. Apparently, these prisoners were a little better fed and therefore stronger than most, and thus able to think of something beyond surviving another day.

Ah, that incident does sound familiar. And I’d bet there are more. I would only say that they are not as well known in popular culture as examples of defiance by Gentiles that occur in movies. The most famous Jewish defiance book and movie took place after the war, though it’s related: Exodus.