When it comes to my mother’s family, the topic of military service is fraught. I’ve written before about the fact that my grandfather Herman Rosenbaum served in World War I but was not rewarded for his service by such basic decency as not being deported from Austria and sent to his death. I’ve also written about how I disliked the idea of my family members as victims. It infuriates me — as I’m sure it did them — that they didn’t have the opportunity to rise up against Hitler.

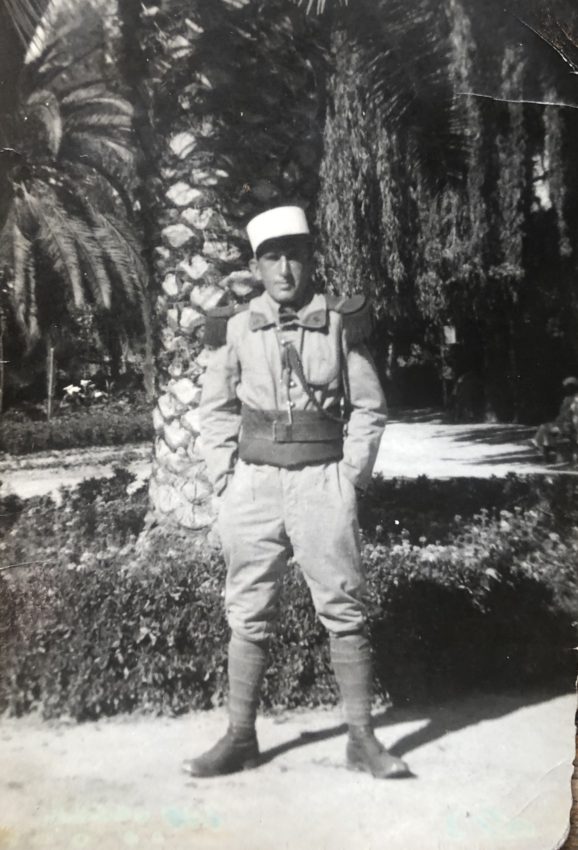

But that’s the Kornmehls. In my father’s family, there was one figure who was able to fight back: my uncle Fritz Jarolim (aka Frederick Braun), who joined the French Foreign Legion. He was a distant, romantic figure whom I met only once; when I did, I discovered then that he spoke English with a British accent. I didn’t know why. Or maybe I did but forgot.

Ah, callow youth, unconcerned about the past.

A fortuitous email

Luckily, many people are far more devoted to the past. Last fall I received an email from a historian of the French Foreign Legion, Frans Janssen, whose specialty is the period from 1930 to 1945. He came across the picture of my uncle Fritz Jarolim on one of the few posts I wrote about my father, and thought that the following details about his enlistment might be of interest.

Fritz JAROLIM

Né(e): le/en 01-07-1906 à Vienne (Autriche)

Carrière: Unité dépôt commun des régiments étrangers (DCRE)

Région militaire: 10e région militaire

Bureau de recrutement: Melun (77)

Sources: Mémorial de la Shoah – Fonds UEVACJEA

Indeed they were.

Because no good deed goes unpunished, I wrote back to Frans and sent him two more pictures of my uncle and two postcards. He proceeded to help me make sense out of the original document and much more.

Frans wrote:

On both pictures of your uncle in the French Foreign Legion, he is wearing the uniform of the 3 Regiment Etranger d’Infanterie (3e REI), freely translated as the 3rd Infantry Regiment (3REI) of the French Foreign Legion.

Identification was easy, because on the collar patches the number 3 is clearly visible. Even if this had not been the case, the pictures would have led to this identification because this unit had a unique uniform feature, two lanyards. On both pictures, your uncle is wearing these. The predecessor of the 3REI received this special honor because of bravery during the First World War. The 3REI itself did not come into action during WW2, but provided significant amount of troops to other units of the Legion that saw action in Norway, France, and later Tunisia.

Back to your uncle. The list he appeared on, from which I sent you the details, is one for men who joined “voluntarily” after the declaration of war to Germany at the end of 1939 until the start of hostilities June 1940.

Most of these men joined the Legion for what was called the “duration of the war,” not for the otherwise mandatory 5 years. Joining for 5 years however was still an option, though at that time rare.

Yet again most of these men actually did not actually want to join the Legion, but the “regular” French Army. However, the Legion was the only formal alternative for foreigners who wanted to join the French Army.

I somehow get the feeling your uncle joined relativity early since he ended up in Algeria and Morocco. Those who joined later, in 1940, were typically kept in special raised units in France.

Because your uncle was Jewish and from Austria, they most likely preferred to keep him in Algeria or Morocco, also in view of the potential consequences if he had been made a prisoner of war. In the case of non Jewish German and Austrians, most of them were kept in Algeria and Morocco because their loyalty was in doubt; even long-serving German legionnaires suddenly became patriotic again after the military successes of the German army. [!]

If I assume that your uncle joined for the duration of the war, the war was over faster than expected, 22th of June 1940.

Soon after, almost all the volunteers for the duration of the war were consequently demobilized. Most of them could not go home either because it was too dangerous or they simply were not allowed. They ended up in a camp in which they were forced to work on projects such as the Trans Sahara Rail Road line.

The likelihood your uncle ended up in such a (work) camp is high.

After the invasion of North Africa in 1942, these camps were liberated, but this still did not mean your uncle or other men could go home.

The Exotic Postcards

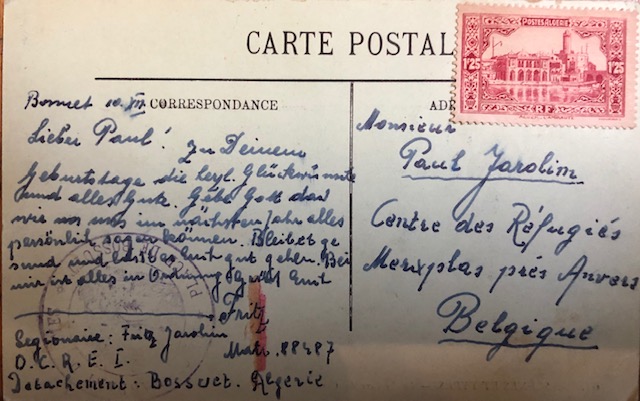

These postcards, sent during the Foreign Legion period, shed as much light on my father’s whereabouts during these years as they do on my uncle’s. This first one was sent by my uncle to my father on December, 10, 1939 from Bossuet in Algeria.

According to Frans:

Bossuet was one of the barracks where typically new recruits were gathered before being transferred to their basic training units. In French it is written Dépôt Commun des Régiments Etranger, abbreviated D.C.R.E. This abbreviation is used by your Uncle at the end. He added an I, which stands for Infanterie.

The translation:

Dear Paul, for your birthday congratulations and all the best. I hope God will grant us that next year we can say this to each other in person. Stay healthy and enjoy yourself.

Here everything is OK. Regards Fritz

According to Frans, the signature, “Legionaire,” indicates the rank of soldier in the Legion.

The address to which the postcard was sent, the Merxplas Camp in Belgium, is the subject of a whole other rabbit hole of research I’ve fallen down into. I’ll get to that in another post.

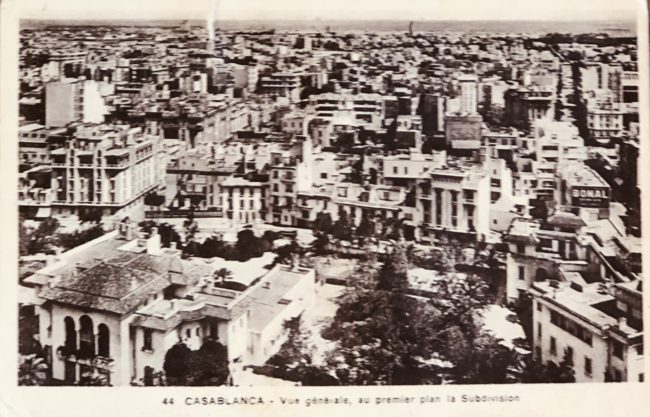

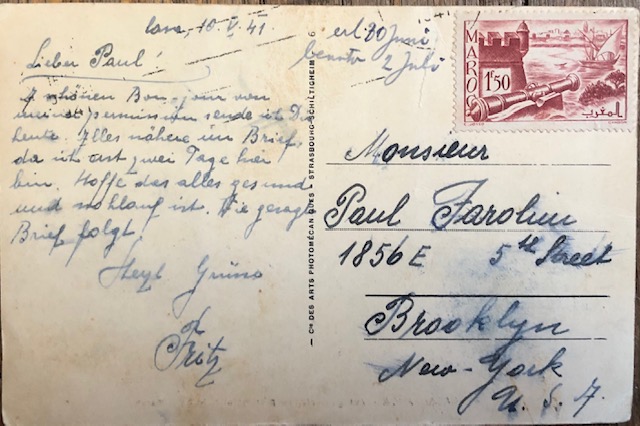

This card from Casablanca — abbreviated “Casa” on the back — was sent May 10, 1941.

Written on the card is, Erh., the abbreviation for Erhalten, which means received, 30th of June (it took the card therefore 1.5 months to arrive) and Beatw., abbreviation for Beantworted, which means answered, 2th of July.

My father had already made it to the U.S.

Fritz wrote:

Dear Paul, a nice “Bon Jour” from my “permission” [I think this means leave] I sent to you today. You’ll find more details in my letter, since I’ve been here only two days. I hope you are healthy and fit. As indicated, a letter will follow.

Kind regards Fritz.

Frans notes, “I get the impression at this moment in time Fritz was no longer in the Legion; otherwise he would have signed with his military address.”

Hail Brittania

This brings me to the picture of your uncle in British uniform. He wears the badge of the Royal Pioneer Corps, the only British Army Unit that accepted foreigners. He might have joined this unit as a way to get out of the camp in North Africa.

Frans generously offered to help me contact the French Foreign Legion to confirm the details of my uncle’s service; he even sent me a sample letter in French that I could use for that purpose, but I did not end up taking him up on it. His knowledge as a historian of World War II is vast, and these details are beyond what I could have hoped for. In the end, I’m just proud that my uncle was able to serve in the war against Hitler. And he looks very dashing, doesn’t he, in both uniforms?

Leave a Reply