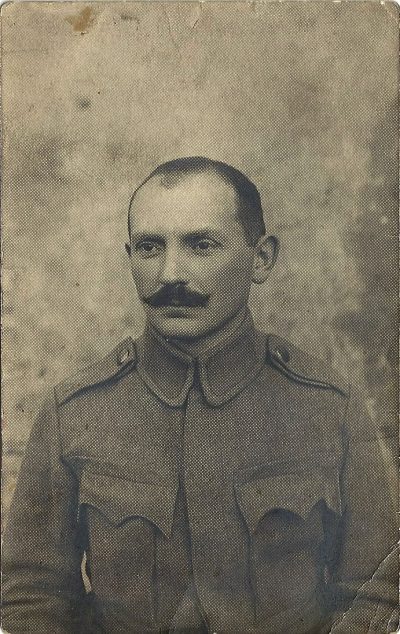

I learned the other day that my current family history subject, Ezriel Kornmehl, had volunteered to serve in the Polish-Bolshevik War in 1921, and that he is listed in the Polish Officer’s Year Book (as Esriel Kornmehl) for 1923 and 1924.

I dutifully set out this morning to look into the details of his military service and to find out what exactly the Polish-Bolshevik war was — which I did, under the name Polish-Soviet War.

And then I realized that I didn’t particularly care which conflict Ezriel had volunteered for.

What I really wanted to write about was Ezriel ‘s misplaced loyalty to the Polish government.

Instead of concentrating on his practice immediately after finishing medical school in Vienna in 1918, he joined the army when he returned to Poland. And whether because he was well educated or because he was a good soldier, he was made an officer.

Yet less than two decades later he was forced to escape Jaslo, where he had lived and treated the townspeople as a doctor, lest he be shot in the woods or sent to be murdered in Belzec. This was the town’s way of saying “Thank you for your service.”

My grandfather, Hermann Rosenbaum, also fought for his country, in his case for Austria-Hungary in World War I. That didn’t prevent the Austrians from sending him to a concentration camp.

Thank you for your service, too.

Yes, Poland had been occupied by Nazi Germany when the worst things happened, but that nation’s history of complicit antisemitism is well documented. Sadly. Don’t even get me started on Austria’s enthusiastic embrace of the Nazis (Update: I tackle the topic a little later in the post Auf Wiedersehen, Pt. 2).

I try to conduct research dispassionately, to focus on my relatives’ day-to-day lives as they unfolded in order to portray them as they saw themselves — in this case as enthusiastic patriots. But sometimes it’s impossible not to let what I know about the future interfere with this process.

Today was one of those days. I couldn’t let go of the notion that, while Ezriel and my grandfather and many other good Jewish citizens fought for their countries in good faith, their countries had neither the will nor the fortitude to fight for their good Jewish citizens in return.

Edie, I agree absolutely difficult to remain impartial about past events in our ancestor’s lives when we are viewing it from what we know today. It’s certainly important to try to get a handle on their mindset but also the mindset of their community and peers and avoid interjecting our own biases. Important but still none the less difficult.

Thanks, Lynn. It occurs to me that I might have just thought these thoughts rather than blogged about them if it hadn’t been for the writing challenge. I hesitated about putting this out there but figured it was part of the process and therefore worth recording.

Thanks again for getting me to put my nose to the grindstone!

Very important column today. (haven’t read earlier ones this week yet but will now). It should be an eye-opener to the families of American soldiers who fought in World War II ‘to help save you Jews’ (as one person put it to me) -not realizing the service that Jewish soldiers and officers had given for their countries.

Perhaps you or another of your readers knows — Wasn’t there also a compulsory draft for Jewish men that could last up to 20 years at some point? Maybe this was in the mid to late 1800’s – I vaguely recall it was the reason that one of my great-grandfathers had left Eastern Europe.

Thanks, Diane. My earlier posts are more “just the facts, ma’am,” no editorializing. I don’t know anything about compulsory 20 year conscriptions — interesting. Maybe someone else will, though.

I don’t see any bias in giving depth to history. Without this view in hindsight, the poignancy of the story is missed. The construction of it in its entirety in book form will be a major challenge, but how so many relatives lives ended in a concentration camp, is unfortunately something the reader should be told. THat you are working it out in the blog is entirely appropriate and useful – this is part of the work that has to be done to get to the ultimate form – and why wouldn’t it affect you?

I have this idea — perhaps impossible to execute — that I’d like to give my family back the lives that the Nazis took away, to see things without the specter of Nazism hanging over them. What happened to everyone might be detailed in an Appendix, or introduction, but I don’t want to give the future more power in my book than it had while things were unfolding.

The pieces of the life history of Ezriel are coming together. You have saved him from being relegated to the side of a family tree without any information about his life. The monthly challenge has already promised to be a successful endeavor….

Yes, I’ve got to admit that — while it’s a toll on my everyday schedule — this challenge has been extremely successful in fleshing out Ezriel’s life (in no small part thanks to your research, of course)!

Very moving post, and entirely appropriate, I think. This question of the future casting a shadow on the past-present of your family is difficult, because it is an important aspect of their story–which is really a tragedy in the classical sense. Maybe you will have to go back and forth between portraying their “normal” lives (most of the time) and (now and then, briefly) informing us of what they were destined to suffer. The perspective may be welcome.

One highly unlikely (it would seem) Jewish soldier, by the way, was…Marcel Proust. (He managed to contrive quite an easy post and never actually fought.)

I had no idea about Proust — how funny! When I get to researching my grandfather, I do want to know more about his service. I got the sense from my mother that he was absent for quite a while and she was affected by it.

My goal is to do for an ordinary family what most writers do for Freud. Of course he was affected by what was going on around him and no one ignores it, but the Holocaust and antisemitism weren’t central to his life until 1938. He is defined by his work, not by being forced to move to London.

Here is a rather interesting, if exhaustive, link to the history of Jews being conscripted into the Russian army in the 1800’s: http://www.yivoinstitute.org/downloads/Military_Service.pdf

Thanks for this, Diane.