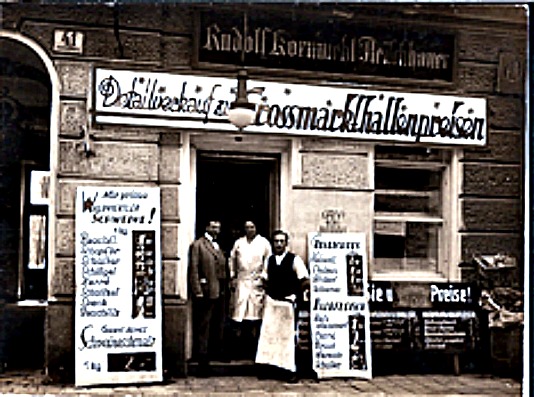

I’ve been trying to imagine what the life of a butcher was like in Vienna in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when my mother’s uncles, the Kornmehl brothers, were in the meat business.

On the one hand, it seems that being a butcher was not a respectable enough profession to allow a Jewish member of the trade into the Vienna lodge of the B’nai B’rith.

But here’s another perspective.

A Very Powerful Clique

According to an article published in The Sydney Morning Herald on October 30, 1897, titled “The Austrian Meat Trade,” butchers in Vienna were living high on the hog, as it were.

Australia, a country with large cattle-raising interests, hoped to be able to export meat to Austria. The Vienna correspondent writes about what has, to this point, been an impediment to such free trade:

The butchers have always formed a very powerful clique. They are all rich, and exercise great influence on the elections to the Town Council. The consequence is that this last has hitherto always managed to thwart the Government’s efforts to enable the people to procure cheap meat. Up until 11 years ago, there was no dead meat market here at all, but only a cattle market for butchers to whom, queerly enough, the price they were to charge to their customers was dictated….in all cases to secure the butcher’s profit.

The arrival of the “dead meat market” — which sounds like a good name for a punk band but would seem to encourage vegetarianism — apparently didn’t have the effect of lowering the price of meat:

For years, the Viennese have been complaining that meat prices are much too high. The consequence of this is that in Vienna, in proportion to the population, the consumption of meat is less than in any other of the large capitals of Europe. The 1,500,00 inhabitants of Vienna do not consume more than 50,000 tons of meat per year — i.e., less than 35 kilos or 75 lbs. per head per year.

(In comparison, people in the U.S. currently consume 270.7 pounds of meat per capita each year — which is more than people in every other country in the world, except Luxembourg. Go figure.)

Was it good for the Jews?

It’s difficult to say whether Jewish butchers benefited from the same political clout as their gentile brethren — or for how long.

It was just around the time that Karl Lueger rose to political power and became the mayor of Vienna. According to Wikipedia:

Lueger was known for his anti-Semitic rhetoric and referred to himself as an admirer of Edouard Drumont, who founded the Antisemitic League of France in 1889. Decades later, Adolf Hitler, a Vienna citizen from 1907 to 1913, saw him as an inspiration for his own view on Jews.

But the historian Léon Poliakov wrote in The History of Anti-Semitism that, in spite of Leuger’s raising of the banner of anti-semitism in 1897, Jews did not actually suffer under his administration. According to the same Wikipedia article, “Other observers contend that Lueger’s public racism was in large part a pose to obtain votes.”

How depressingly familiar is that?

The Middle Ground

Looking at the dates, however, it seems likely that any power Jews in the clique had would have been enjoyed by my great grandfather, Chaim Kornmehl, from whom his sons inherited the butcher businesses. Siegmund Kornmehl — Freud’s butcher — was born in 1868, his brother Martin in 1875, the third son, Rudolph, in 1880.

According to No Place Called Home, a memoir by Gigi Michaels — one of my newfound family members and Rudolph’s granddaughter — Rudolph and Molly Kornmehl lived the typical Viennese middle class life, lounging in coffee houses and enjoying the culture the city had to offer. They had a country home, skied in the mountains in winter, and had a housekeeper and nanny for their children. But, according to Gigi, both of the couple:

… worked hard managing the three butcher stores they owned…. Three times a week Rudolph got up at four in the morning to the meat market where he often argued for the best prices and freshest meat. He knew that his customers were true to him because he carried the finest quality meats.

Rudolph and Molly don’t sound like they benefited from being political insiders or that price-fixing was still in effect. Rather, they seemed to be a couple that lived well because they both worked to run successful businesses that cared about customer service.

I’d be interested to know if Viennese meat consumption rose in the 20th century; I’ll try to find some statistics. Given the popularity of pastries with schlag (whipped cream), the citizenry might have been better off when the price of meat was artificially high and they had to be a bit more abstemious.

Terrific article! Very well written, well researched, and very entertaining.

What a nice thing to hear on a Monday morning! Thanks, Lee.

Loved the description of ‘middle class’ life – lounging in cafes, skiing – plus the hard work – very evocative- almost having the vicarious experience of being there living the life!

Very interesting and informative article! I enjoyed taking a step into the past and also seeing the similarities you’ve found to certain aspects of our present. Luxembourg as the second heartiest meat-consumer after us? That’s a surprise. I would have thought of Argentina (beef-raising country) or New Zealand (sheep). As for Austria itself and its current meat-consumption, you’d think that decades of lower meat consumption might have ingrained certain culinary and dietary habits, but then habits change (witness China’s–unfortunate–rising consumption of meat/beef).

I look forward to more!

I know. Luxembourg was unexpected. But NPR must be right!

That’s another topic for study — how many generations it takes for consumption to catch up with availability…

Sorry, but I got lost back there near the beginning, wondering about what they sold in the live meat market–as opposed to the dead meat market. And then you mentioned mit schlag, and I was transported right back to Vienna where they take their pastries so seriously that there was a years-long judicial battle over the right to claim Sacher Torte. That paralleled a similarly vicious fight over the right to market Mozart balls. (And wouldn’t Mozart have had some scatological comments about the name of that candy!) Wonder if anyone sued over sausage?

That’s the wurst comment I’ve seen, my friend… but in a good way. Mozart balls? Do tell!