As the 2018 Family History Writing Challenge comes to a close, I observe that I solved a few mysteries; came up with several more; and reaffirmed the importance of genealogists who pass along stories rather than genes.

A Divorcee and a Bastard (That’s A Technical Term)

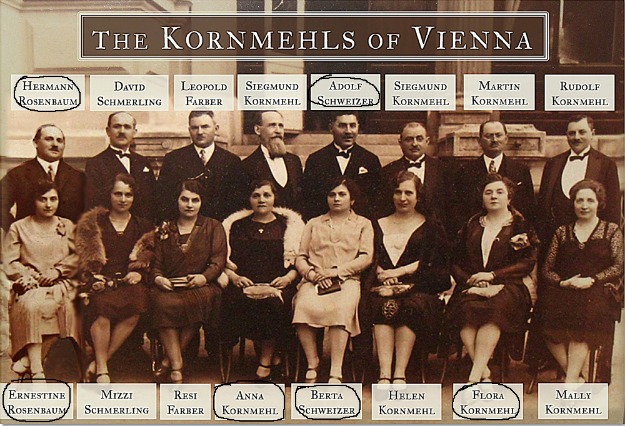

It seems that my great uncle and aunt, Adolf and Bertha Schweizer — aka Abraham Rittman and Berta/Bella/Biela Kornmehl-Singer-Schweizer or Schweitzer — may have been the black sheep of the family, although Adolf shared in the family profession: He was a butcher. Bertha was a divorcee and Adolf may have been illegitimate; at the least, he didn’t take on the name of the man that his mother was married to until many years later.

They adopted a child, Erika, when they were in their fifties.

Why did Bertha and her first husband, Samuel Singer, divorce? Was it because she couldn’t have children? Was Bertha cheating on Samuel with her husband-to-be? Was Adolf’s assumption of the name of his mother’s husband connected to the fact that they were adopting a child?

I haven’t answered these questions — and many others, such as what happened to Erika — in part because I got sidetracked to other family members via the issue of late life adoptions, and in part because I got to the point where their story became too difficult to contemplate: The years after 1938 in Vienna when the Schweizers and my grandparents and Anna Kornmehl and two of her children and Flora Kornmehl and two of her children as well as a daughter-in-law and grandchild kept moving from apartment to smaller apartment shared with more and more people until they were finally sent off to be killed.

That’s what happens when one of the main sources of information about your subject is an emigration questionnaire filled out by people who don’t want to leave.

So, for example, I started tracking down the relatives Adolf Schweizer listed as potential sponsors, people who would vouch that the couple would not become wards of the state. But then I realized that it didn’t really matter who they listed and what their relationship with them was because their pleas for help from these relatives went unheeded.

I’ll return to the Schweizers, and to others whose stories I’ve neglected. I just need a Holocaust break.

Who Am I to Tell Their Story?

It would be nice if I could locate Erika’s kin, or someone else close to the Schweizers, to research the couple’s story, but I’m not banking on it. As I said yesterday, if you want a story told, tell it yourself.

Anyway, who better to tell the tale of outsiders than another Jewish family outlier, a happily single divorcee with no children? Back in 2012, I wrote a post called Sex & the Single Genealogist that touched on these issues. I’m glad I had the chance to remind myself and others who might need a refresher that passing along family stories is as important as passing along genes.

I’ve made a note to myself to read your whole writing challenge series. As a childless widow with no living (close) family, I’ve thought genealogy was silly. Silly to continue I should say. Thanks for pulling me up short.

Thank you for coming by, Sue! I hope you pursue it if you find it interests you.

Wow. Again you touched me. I always thought that that’s why my dad wouldn’t talk about family – because most didn’t make it. It has been surprising for me to find so many, like your parents and the other Kornmehls, who DID make it. So let’s celebrate that 10 out of the 16 pictured who somehow survived…but so sad about the 6 who didn’t, and all the rest. Thank you for keeping alive what little we have of them: their names, a few photographs, and these few memories.

Elaine, thank you so much for this; it means a lot that you appreciate what I’ve been doing. I really like your positive take, honoring those who didn’t make it, celebrating those who survived.