This is Day 6 in the Family History Writing Challenge.

I tend to be irreverent in my family history discussions — both because I tend to be irreverent about everything and if I didn’t laugh about certain topics, I would cry. This last was the case with the discussion of Samuel Singer’s military service (or potential therefore) in the last post.

Other Members of My Family in the Austro-Hungarian Army

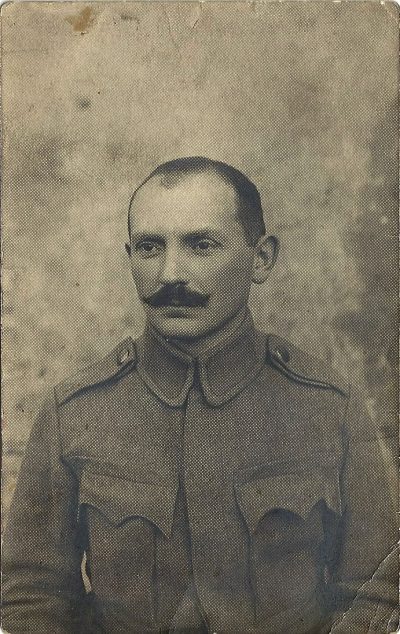

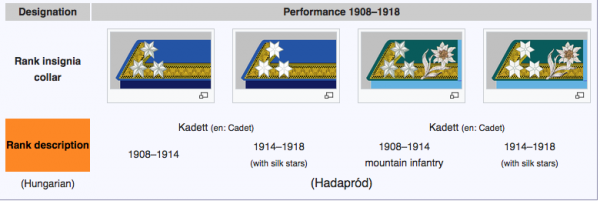

My mother was an only child and she sometimes talked about being a lonely child. She adored her father but, she complained, he spent many years of her childhood in the army. I have two pictures of my grandfather as a soldier, one with and without my mother, one with and without the stars on his collar–not to mention with a less flamboyant mustache. This Wikipedia article about rank insignia in the Austro-Hungarian armed forces would seem to suggest he was a sergeant (which my mother’s annotation on the back of the photo confirms) but that he’s wearing the stars in the wrong place — on his collar rather than his sleeve.

But the article was complicated and treatises on military rank tend to make me glaze over.

Insignias with Edelweiss?

That said, some of the pictures in the article explained the title of a HuffPost article about the Austro-Hungarian military, “Edelweiss and Fez: Officer Diversity in Imperial Austria.”

Yes, one unit of the armed forces bore a symbol of the Austrian National Flower–if Austria had an official national flower before the movie Sound of Music.

The HuffPost article notes that Austrian Jews rarely thought of in martial terms — intellectuals such as Freud, Schoenberg and Schnitzler– all became officer candidates during their military service. Which was not atypical of the time.

According to the story:

Up until 1918…no other army in the world produced more Jewish officers than the Austrian-Hungarian military….In 1897, a census revealed 1993 Habsburg Reserve Officers who classified themselves as Jewish, which constituted an astounding 18.7 percent of the entire Austrian-Hungarian Reserve Officer Corps.

It goes on to explain:

The reason for the high number of Jewish reserve officers is the proportionally higher level of education of people with a Jewish background in the empire. Jews constituted around 15 percent of the student population at universities in imperial Austria. Similar to today, only students with a Matura or secondary education degree were eligible to join the army as officer candidates.

Thus the participation of Freud, Schoenberg, and Schnitzler. The article goes on to say:

In 1914, the reckless decisions of an inept Austrian military command nearly wiped out the professional officer corps in various failed offenses on the Eastern Front in the first few months of World War I. Reserve officers had to rise to prominent positions and lead the army for the duration of the war. At the end of the First World War, there were 24 Jewish generals serving in the imperial and royal army. Jewish officers commanded troops in such crack outfits as the k.k. Kaiserschuetzenregiment 1, “the Imperial Hunters,” a mountain warfare unit sporting an Edelweiss Flower insignia on their caps, who were recruited in Tyrolia.

Talk about a feather — or a flower — in your cap.

From a Jewish perspective, serving in the army was an “opportunity to exhibit…patriotism and counter anti-Semitic prejudices. Behind this lay the desire to earn membership and respect by demonstrating Jewish commitment.”

Which leads me to the part of the story I loathe.

Thank You for Your Service

I’ve already covered this topic, for the 2013 Family History Writing Challenge, as it happens, and also on Day 6 (cue “Twilight Zone” music). In my post “Pondering Jewish European Patriotism,” I said:

What I really wanted to write about was Ezriel [Kornmehl’s] misplaced loyalty to the Polish government.

Instead of concentrating on his practice immediately after finishing medical school in Vienna in 1918, he joined the army when he returned to Poland. And whether because he was well educated or because he was a good soldier, he was made an officer.

Yet less than two decades later he was forced to escape Jaslo, where he had lived and treated the townspeople as a doctor, lest he be shot in the woods or sent to be murdered in Belzec. This was the town’s way of saying “Thank you for your service.”

My grandfather, Hermann Rosenbaum, also fought for his country, in his case for Austria-Hungary in World War I. That didn’t prevent the Austrians from sending him to a concentration camp.

Thank you for your service, too.

I try to conduct research dispassionately, to focus on my relatives’ day-t0-day lives as they unfolded in order to portray them as they saw themselves — in this case as enthusiastic patriots. But sometimes it’s impossible not to let what I know about the future interfere with this process.

Today was one of those days. I couldn’t let go of the notion that, while Ezriel and my grandfather and many other good Jewish citizens fought for their countries in good faith, their countries had neither the will nor the fortitude to fight for their good Jewish citizens in return.

What a moving and tragic story. And a wonderful, wonderful picture. I frequently am very glad that my ancestors did not know what lay in store for them as I look at one of their photographs in happier times. Certainly not as drastic as concentration camps, and not having the people they had been helping turn against them. I understand your reluctance to talk about that part of their lives, but we do need reminding from time to time.

Thank you for coming by and commenting–and for your nice words. Yes it is a good thing in most cases that we can’t peer into the future, though occasionally it might be nice to know if things turned out well.