As my CV will tell you, I am an editor as well as a writer. Correcting spelling and grammatical errors is second nature; I’m one of those people who proofreads restaurant menus (though not, you’ll be relieved to hear, out loud when I’m with other people).

So perhaps it’s fitting that I should end up contemplating the fate of my namesake aunt because of a typo on a deportation list.

Denial, Denial

I’ve always had a complicated relationship with memorials to Jews killed in the Holocaust. Mainly, I avoid them. I suspect I inherited a version of that attitude from my mother, who asked to be cremated when she died. Her rationale for wanting to do something that goes against the Jewish religion? “If it was good enough for my parents, it’s good enough for me.”

To my mother, ending up in an oven was shorthand for Holocaust death. In fact, she didn’t know precisely how and where Ernestine and Hermann Rosenbaum were killed and never wanted to find out. When I was in high school, my mother received a book in the mail from a death camp; I can’t recall which one, and I don’t think we ever knew why she got it. It sat on the kitchen table, unopened, for weeks, until my mother finally looked to see if her parents’ names were in it. They weren’t. (As I later learned, my maternal grandparents died in Riga.)

The Holocaust Memorial in Vienna

Along those lines, I’ve always aimed to focus on the everyday lives of my relatives in this blog, not their deaths. I’ve stuck to that goal for the most part. But on a Facebook group I joined in pursuit of reclaiming Austrian citizenship, I found a post about the upcoming dedication in Vienna of a memorial to the Austrians killed in the Shoah. I was curious to know if several of my closest relatives were included.

I found my mother’s parents and my father’s brother Richard, but not my father’s sister, Edith. I checked the DOEW database from which the monument’s names were drawn; she was not listed there.

I wrote to the DOEW with a screenshot of my aunt’s information from a reliable genealogical source, her date of birth and the date of her deportation to a place called Litzmannstadt, which I had declined to investigate. I got back the following answer within 24 hours:

Thank you for your email and making us aware of this mistake. We have looked into this and realised that the name of your aunt was included in our online database as “Edith Jarolin“. This version of the name was depicted in the transport list to Litzmannstadt as well as in another document. However, I have looked into this case closely and could verify that the version of the name in the sources was false. I have therefore changed the entry of your aunt to the correct version „Edith Jarolim“ in our database of victims.

I have also passed this information to the Shoah memorial wall.

The Shoah Memorial wall is a project initiated by private organisation. We have made the organisation aware of the fact that unfortunately this work of searching for the names of those murdered in the Shoah will never end and that there will always be names and changes to add in the future. Therefore, there will be enough space on the memorial to be able to include additional names or new corrected version of names in the future as well.

The name of your aunt will therefore also be engraved in the correct version.

The Jarolim Family

I very much appreciated this response, knowing my aunt was being commemorated—and possibly twice on the same monument, though I don’t mind if she’s only there as “Jarolin”; misspelling her name on a deportation list was the very least of the indignities to which my aunt was subjected.

But this information led me down a path I didn’t want to take: contemplating Edith’s last days.

Let me backtrack.

My grandfather Ignatz Jarolim was one of the few members of my immediate family not uprooted or killed by the Nazis. He died in 1919 of bronchial pneumonia, no doubt a victim of the flu pandemic. That left my grandmother Mathilde/Malvina/Margarete Brown Jarolim (I’ll get to that in another post) raising four children — Edith (b. 1899), Richard (b. 1901), Paul (b. 1903) and Fritz (b. 1905) — on her own. That’s four children who lived at home, all unmarried, until 1938, when the Nazis occupied Austria.

The plan was to send the men ahead to find work in a country that wasn’t under Nazi control; they would wire the money for boat fare back to Vienna to save those left behind.

My uncle Fritz joined the French Foreign Legion. My father and his brother Richard ended up in Merxplas, a Belgian refugee camp. I’m still not sure how my father was able to get to America while his brother was sent back to Austria, later to be deported to Auschwitz.

Grandmother Mathilde died in Vienna on March 29, 1941, cause unknown. She was buried next to her husband in Zentralfriedhof. I have a photo of their very impressive gravestone but by the time I got to Vienna in 2014, the large monument had disappeared among the ruins.

And then there was one: my Aunt Edith. She was deported to Litzmannstadt less than eight months later, on 10/19/1941. It was a blessing that her mother didn’t live to see it—or get taken along with her.

My Mysterious Aunt

So who was my Aunt Edith in life? I would love to be able to tell you but, sadly, I don’t know.

From the forms they filled out in an attempt to exit the country legally, I learned my uncles’ professions: Fritz was a furrier/tanner. Richard was a shoemaker. My father was a dental technician.

But my grandmother and aunt did not fill out exit forms, so I have no idea what work they did outside the home, if any. My father never said; he didn’t talk about his sister at all. My mother told me that when he learned, after the war, that Edith had been killed, he had a kind of nervous breakdown. It’s easy to understand his pain. As per the plan, my father scraped together enough money to get boat fare for his mother and sister to escape, but the borders closed before it could be wired over.

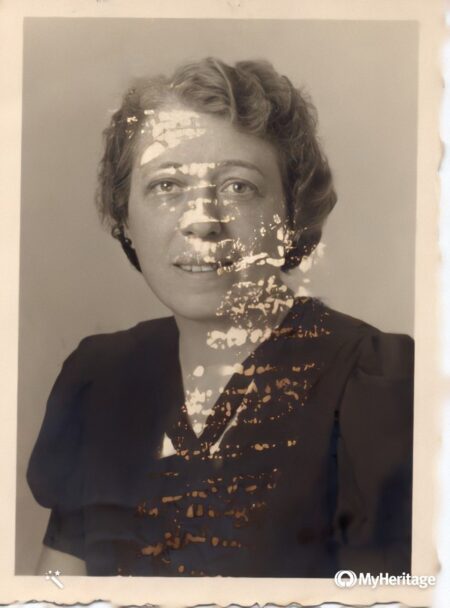

I have only three pictures of Edith, one at age 39, two at age 41.

The blurry picture in the woods, above, always gave me the creeps. Perhaps because the trees are bare and I can’t explain the dark square below her feet. Maybe because the coat and hat were set aside and yet remain in the picture, which seems ominous. I imagine it’s just tricks of the light and the (unknown) photographer being unfamiliar with focussing a camera or framing a picture. This was taken a year before Edith’s mother died, so if Mathilde is to blame, I apologize for any disrespect.

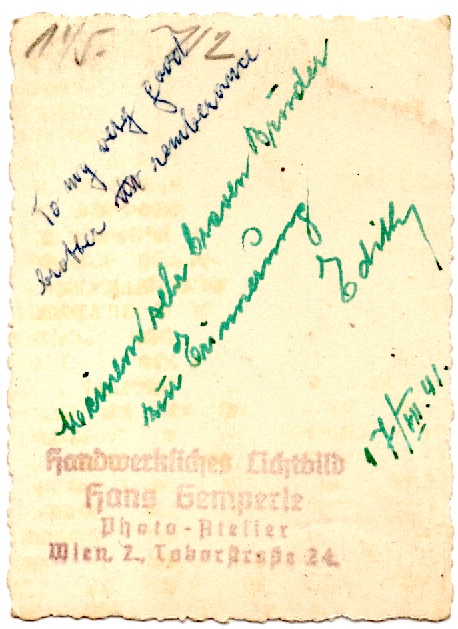

On the other hand, Edith looks nice in the picture with her family. Did she spend her days keeping house for her brothers, along with their mother—thus obviating the need for the men to marry? In any case, I know that she loved her brother Paul. The message on the final picture she sent him says so.

The Last Picture

The handwritten translation on the top left was that of my mother; the green ink was my aunt’s. The date—a combination of Roman and Arabic numerals—was July 17, 1941.

Edith was deported to Lintzmannstadt three months later.

Which brings me back to the typo-ridden transport list. This time, I learned that Lintzmannstadt was better known as the Łódź ghetto. My aunt either died of starvation there or was sent to Chelmno, “the first stationary facility where poison gas was used for the mass murder of Jews”—and yet another place I didn’t want to think about.

So I decided not to.

Instead, I asked my Facebook friend Steve Hanley, aka the Psychogenealogist, if he knew how I could get the picture of Edith restored. Although it’s not the main focus of his blog anymore, he generously offered to help by calling in a favor from a friend.

They did a wonderful job. And so I will leave you with this version of my lovely aunt, the one she wanted her younger brother to remember her by.

Such a poignant tribute to your aunt and namesake Edith. May we all be so remembered by our nieces 80 years later!

Thanks, Laura! I wish I knew more but I’m glad that I could commemorate her in this small way.

This is very moving, Edie. She may have known she was doomed at the time of the photo. Why would she have had a formal studio photo taken for her brother if she thought she would be seeing him soon? Thank you for writing about her.

Thanks, Lydia. It is rather mysterious, isn’t it — including the fact that she spent money on a formal portrait in these difficult times; at that point, she was no longer living in the flat she had shared with the family, but was crowded in with other displaced Jewish families. And no Jewish businesses were allowed to exist by 1941–all were “Aryanized” starting in late 1938 — so she would not have gotten any kind of sympathy discount from the photographic studio. And she would have been obviously Jewish, required to wear the yellow star, though that is not in the picture.

Also — she probably knew that the borders had closed and so knew that her brother would not be saving her.

So well told Edie. Her life had, and has, meaning. Just looking at her picture shows she was a kind person.

Thank you, much appreciated.

I enjoyed reading your aunt’s story! In the family photo, I see a definite resemblance between your aunt and you in the oval shape of her face. I never knew you had an uncle in the French Foreign Legion. Have you written about that before?

Thanks, Marcia. I definitely take after my father’s side of the family; my mother’s side tend towards round faces. As for my uncle, I should have linked to that post in the first place. I just corrected that in the post, but here’s the link separately.

I believe my relatives who remained in the area of western Poland, that my maternal grandparents had left in the 1880’s, met their fate at Chelmno. Thank you for this remembrance, which is reminding me of the incomprehensible events that took place there that I only learned about as an adult and still have a hard time fully grasping. It only became real to me when I came across a photo of a girl in a detainment camp near there who was the spitting image of my mother at that age.

In another matter, speaking as a photographer, if you are questioning the square shape behind Edith’s feet, I believe that is the shadow cast by her dress from the sunlight. The sun was almost directly overhead. I see the more irregular shadow cast by her coat is at the same angle, and the shadow cast by her face, they are all at about the same angle. As to why the coat and bag are included in the photo, the person taking the photo might have intended that the photo be cropped later. Perhaps they did not know how to use the camera and adjust the focus and had to stand that far back to take the picture.

I’m sorry that your relatives likely ended up in Chelmno too; I didn’t look into it too deeply but it seems nightmarish.

Thanks for your insight as a photographer re: the shadows on Edith’s face and clothing and underneath her. And yes, it’s definitely a problem with the photographer who didn’t focus the camera and didn’t know enough to move the coat and hat out of the frame.

As always..I learn so much from reading about your family and thru

Your stories…..I always think of your father as dignified, soft spoken and kind….this is a wonderful; tribute to your Aunt Edith…..and

It is so great that you got her name corrected….I just love that!

Thanks Sharon. It’s always wonderful to read the reaction of the few people around — like you! — who actually knew my father.

That was most interesting and heartfelt. There’s so much we don’t know and will probably never know. And what we do know, we never want it to happen again.

Thanks, Karyn. We definitely don’t want it to happen again.

Edith was beautiful. What a poignant tribute to her. Sigh.

Thank you. Sigh indeed.

A lovely tribute to a brave lady.

Someone else noted the resemblance between you and your aunt, which I also noticed immediately.

Thanks, Kate. I’m beginning to see the resemblance myself…

Thank you, Edie, for sharing this difficult story so sensitively. I found your mother’s reason for being cremated so poignant.

Thank you, Anna,

Aunt Edith was my aunt, and I had never in a million years believed such a thing would be made into a movie. Of course Aunt Edith is the “mystery” here, but that’s only because we don’t know why she is so important. When you think of movies with murder plots, I want to tell everyone about The Great Ghost Ship (2014), which is about a couple who buy the ship they suspect the ghost ship from and find themselves a new life. There’s even this scene in it, not on-point for me, with our family having lunch at a restaurant, including my aunt. And then there’s this sequence that involves some kids finding what used to live right inside of their mom. But that’s another whole thing I have to talk about. You can read the movie review by clicking here, but also watch the trailer if you would like to see Aunt Edith in all her “uncanny” glory:

A quick story… The last time I had been watching some TV shows, one of them showed old friends like Uncle George and the Gang, but on Netflix (RIP).

I am keeping this odd comment to show what spam filters will permit. I understand why. I almost thought this word salad was legit too (I removed the link, of course…).