When I talk about my parents’ forced departure from Vienna, I generally focus on the tragic outcome: the death of almost all their immediate family members, except for my father’s brother, Fritz.

On this Father’s Day, I’d like to focus on the bravery — combined with what must have been ingenuity and a bit of luck — that got Paul Jarolim to America from Nazi-occupied Austria.

The known knowns

My father talked very little about his journey to America; much of what I learned I extrapolated from historic records/old family pictures and postcards. Here are the things I know for sure:

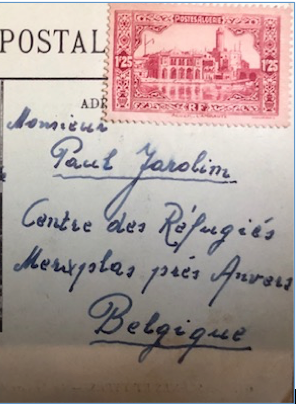

- Paul Jarolim left Austria with his brother Richard some time in late 1938 or early 1939 and ended up in a Belgian refugee camp.

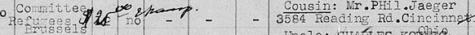

- Aided by the Committee for (Jewish) Refugees, my father sailed from Brussels to New York on the SS Pennland, arriving on December 23, 1939 (his 36th birthday!). He was without his brother Richard. He listed Phil. Jaeger of Cincinnati, Ohio on the ship’s manifest as his sponsor, his final destination as Ohio.

The Key Questions

- How did my father and his brother Richard get out of Austria and end up in Merxplas together?

- What exactly was the Merxplas refugee camp? The picture in the next section, below, shows a group of men who look rather cheerful.

- How did my father get out of Merxplas — and on to the S.S. Pennland — without his brother, who was sent back to Austria and, ultimately to his death?

- What is the Committee of Refugees, Brussels, listed as the organization that helped my father?

- Who is Phillip Jaeger of 3584 Reading Road, Cincinnati Ohio, listed as my father’s cousin in the ship’s manifest?

- How did my father get to stay in New York rather than move on to Ohio?

A Few Answers That Raise More Questions

My online research led me to a great deal of information on Merxplas, including an article on the topic written by Olivier Hottois, a curator of the Jewish Museum of Belgium, as well as an entire book devoted to the camp by one of its inhabitants, Joseph Fabry (formerly Epstein). Under the name of Peter Fabrizius, Fabry/Epstein also devotes a few pages to his life Merxplas in a larger book on a different general subject. The camp is part of a fascinating social experiment, which I plan to write about in more detail in a future post.

But Hottois’s article is largely based on Fabry’s book, which is specific about his personal experience but says nothing about most of the camp’s other prisoners or about the camp’s dissolution. Indeed, Fabrizius writes in One and One Make Three:

I was the first one to leave Merxplas… Our camp had served as a model for others, including a much-needed camp for families. No more than half a dozen succeeded in emigrating abroad from Merxplas. The rest disappeared when the Nazis occupied Belgium on May 28, 1940. [emphasis mine]

If that is accurate — I have no evidence one way or the other — my father was one of the half dozen. How and why did he manage to survive? He spoke generally of a quota system, and we know that America restricted the number of Jews the country would accept (a total of about 27,000 in 1939). How did my father manage to get one of these much coveted visas, and not his brother?

The answer may lie in the sponsorship of my father by Philip Jaeger, who may or may not have attended school with him.

With the help of a member of a Jewish genealogy Facebook group, I found a Dr. Philip Jaeger of Ohio, who had a dentist brother named Samuel who lived in the Bronx. Being a contemporary of my father, born in 1903, Philip is long gone.

I did manage to track down one of Philip Jaeger’s two sons, Irwin, who is 88. Sad to say, he did not have a clue about how his father might have known my father, except that he attended the University of Vienna (my father did not, but they might have been in the same social circles). Nor could he provide any pictures of his father in Vienna.

Irwin Jaeger did confirm that he did not believe that we were related, which did not surprise me. A lot of people claimed kinship with people for the purpose of getting visas, and the Americans did not have genealogists on hand to confirm claims. They only wanted proof that people who came into the country would not be freeloaders.

As shown in the photograph of a detail of the ship’s manifest, above, my father had $25 in his possession to confirm that — plus the name of a sponsor.

Next Steps

I’m hoping to find the records of the Committee of Refugees, Brussels, in order to find out when Richard and Paul Jarolim entered the country — and under what aegis Paul left. So far, I’ve had no luck with a national or international organization of that name or description. I just found an item listing records of Merxplas camp at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; I will explore that next.

I’m also going to see if Samuel Jaeger, the dentist who lived in the Bronx, has any descendants who might be able to help me figure out the connection between his family and mine. My father was a dental technician, so perhaps that was the reason they rubbed shoulders — or teeth.

All suggestions about where else to look to find out more about my father’s journey are welcome.

As I mentioned, I plan to write more about the history of Merxplas and also of the ship my father sailed on in future posts. In the meantime, I leave you with evidence of a not-so-unhappy ending to these adventures, one that pays tribute to fatherhood. That’s my sister, not me. I was a second child and my parents were no longer interested in taking pictures by the time I came around (no, I’m not bitter at all).

Thanks for this, Edie. The name Joseph Fabry rang a bell from my research on Viktor Frankl, so I looked up the name. It may not be the same Joseph Fabry since, although he was in a refugee camp in Belgium, according to Wikipedia, there’s no mention of a book about the camp. Thought you might be interested. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Fabry

Thanks for this, Anna. It is actually the same one — and in fact I thought of you when I saw that he wrote about Viktor Frankl. The book about the camp is not widely distributed, I don’t think. The blurb for the other book that I quote from, One and One Make Three, mention’s Fabry’s role as the founder of the Institute of Logotherapy.

Fascinating story. Can’t wait to hear what else you can dig up.

Thanks! I’m exhausted even thinking about it.

More pieces to the puzzle, more questions!

Always more questions!

Glad to read this now

Thanks, Diane!

Edie:

You are brave and an accomplished writer/editor. I will not be surprised at what you are able to unearth. Thanks for the information.

Thank you, Maxine! So much to learn about all this, the information well seems bottomless.