I admit it: It sometimes takes me a while to unpack from a trip. On my recent return to Tucson from New York, I didn’t need the winter clothes I’d brought with me (nyah nyah); only an underwear shortage inspired me to retrieve the contents of my suitcase. It sometimes takes me even longer to unpack my experiences, since there’s never any shortage of stories — only some of them dirty laundry — to air.

In my last post I talked about a visit with a childhood friend to the new (to me) Neue Galerie and associated Saborsky Cafe, where I sampled a cake that was a little short on marzipan but more than compensated with schlag. I pick up this story with another museum, more Viennese culture, several new (to me) family members, and more pastry. I’m sorry if I’m a little predictable.

Cinematic Vienna

Sometimes news takes a very circuitous route to Arizona: I heard via my new blogging friend, Dorothea, who lives in Zurich and writes about Vienna in 1900, that the Museum of Modern Art was celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna with a cinema series about the city. So when Elaine Schmerling — whose mother, Esther, married the son of one of my great uncle David Schmerling’s brothers — suggested we go to MoMA, I jumped at the idea. I’d met Elaine twice before, in Scottsdale (see picture, above), and was pleased that Esther had agreed to come with her to Manhattan from Delaware for a family get together.

It was a Sunday, and MoMA was packed to the point of discomfort. Still, it’s impossible to dislike a place where, practically every time you turn around, you see another picture ripped from the headlines of art history: Van Gogh’s “Starry Night,” Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” Rousseau’s “Sleeping Gypsy”… And a Klimpt, “Hope II,” maybe not the most famous one but certainly a beauty:

After all the shuffling around and two forays into crowded cafes — one for a salad at lunchtime, one for a post-art pastry, which was good if not blogworthy — it was a relief to settle into the quiet of the theater for that afternoon’s offering in the film series, Vienna Unveiled: A City in Cinema. According to the website, the series:

…spans the late 19th to the early 21st centuries, from historical and romanticized images of the Austro-Hungarian empire to noir-tinged Cold War narratives, and from a breeding ground of anti-Semitism and European Fascism to a present-day center of artistic experimentation and socioeconomic stability…[including] masterworks and rediscoveries of fiction and nonfiction, and a rich selection of newsreels and actualités, avant-garde films, and home movies.

I almost wanted to walk out after the first film, “Vena” (1945), and not because it was grainy and its subtitles were hard to read. MoMA’s press release about it says:

On April 13, 1945, in the dramatic final months of the Second World War, the Red Army liberated Vienna from German occupation [emphasis mine] following a two-week offensive. This film by renowned Soviet documentarian Posel’skij deftly captures the emotional impact of one of history’s defining moments.

Um, liberated Vienna from German occupation?

Um, liberated Vienna from German occupation?

I don’t doubt that the film related the historical events of the Vienna Offensive accurately, down to the scenes of the Viennese dancing in the streets. But I’ve become all too familiar with the big picture: Austrian complicity in the Anschluss (see Why the Sound of Music Doesn’t Play Well in Austria). So I played a tiny violin during the half hour I spent watching the Viennese being released from the Nazi subjugation that they had embraced.

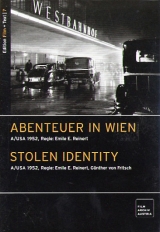

But I’m glad I stayed for the second film, “Abenteuer in Wien” (1952), which was far more entertaining; MoMA showed the Austrian version with subtitles, but an English-language version was directed simultaneously and released in the U.S. as “Stolen Identity.” The Wall Street Journal reviewer describes it as “a near-forgotten Austrian noir that has been compared to ‘The Third Man,'” and according to Edition Filmmusem:

Abenteuer in Wien / Stolen Identity is a forgotten little masterpiece… The dark and shaddy [sic] pictures of Vienna are far away from the usual Vienna cliches. All characters are lost, fleeing the past towards a better future. Neglected by the film critics, Abenteuer in Wien / Stolen Identity was the first Austrian-American co-production since the introduction of sound film and the first Austrian production filmed in two versions: a German version and an American version with different actors in the main parts.

I didn’t quite understand the pairing of the two films on the program. I’m guessing that “Vena,” showing the destruction of sections of Vienna, prepares us for the scenes in “Abenteuer” of chases — and eventually romance — among the ruins.

Hungry for Hungary — And Family Connection

I’ve been virtually exploring Vienna the city on my own in some ways, but when it comes to research about the family members who lived there, the major event of the New York visit was meeting Jill Leibman Kornmehl. An essential — and continuing — contributor to this blog, Jill has written several guest posts, including the Far Flung Kornmehl Family. We don’t have Hungarian relatives, but in recognition of the family’s pastry shop-owning past (see picture next to title) — and of the convenience of Columbia University to Jill’s commute from the city — we met at the Hungarian Pastry Shop:

At our get together, a wonderful culmination to our years of corresponding, Jill provided me with a box of family documents from Vienna, which I’ve slowly been going through. Most of them have to do with liquidating my family’s property, especially Siegmund Kornmehl’s butcher shops, one of them in the same building as Sigmund Freud’s living quarters and consulting room. Many of them have stamps of the Reich with swastikas on them. They’re also signed “Heil Hitler!”

The exclamation point is in the documents themselves; it is not my commentary. But it does inspire one.

I’ve mentioned the release from the so-called German occupation depicted in “Vena.” The liquidation documents I’ve been perusing are dated within months of the Anschluss; the alacrity with which Jewish property was seized is chilling. And while it could be argued that it was necessary to acknowledge the Führer in all correspondence, the exclamation point seems a bridge — or punctuation mark — too far, suggesting enthusiasm for, rather than just compliance with, Nazi policies.

Then again, maybe it’s just the standard visual representation of the Nazi salute. Who says grammar doesn’t matter?

Love how you tie everything together! Although we got from NJTransit to our car just as the snow started falling (and drive home took longer than I though!), we had a lovely day and were so glad we got to see you! The film at the end was icing on the cake. (And I’ll do a better cake at a real pastry shop next time like you did!)

Thanks, Elaine! I’m glad you enjoyed it. It was great to meet your mother too.