For most of my week in Vienna, my experience of the city was so positive as to be a bit surreal. I remembered Vienna from the early 1970s — the only time I’d visited before — as being gloomy and dour.

I also imagined that, given what I’d learned over the last few years about my family’s history, I would be coping with a lot of difficult emotions.

Not so.

The city, several residents told me, has changed dramatically since the Iron Curtain fell in 1989. It wasn’t my imagination that Vienna used to be depressing when it was backed up against depressing Communist countries, they said, or that it has since shared in the tourist bounty that resulted from the area’s opening up.

In fact, that’s pretty much how I felt, like an appreciative tourist, visiting one of the world’s great cities, indulging in its famous indulgences. Even when I was taking pictures of my family’s former properties or visiting the graveyard where several members are buried (theoretically), I felt distanced from any negative feelings. I was looking at ordinary lives (and deaths), not thinking about 1938 and the Anschluss. I had no reason to.

Except on my first day in the city, and I avoided thinking about that. Until now.

Who the Heck Is Karl Lueger, Anyway?

A bit of background.

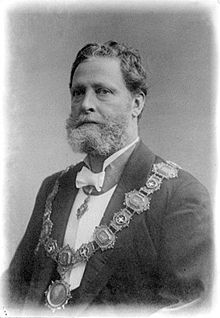

Until I began researching Vienna and my family history, I had never heard of Karl Lueger. But his name kept cropping up in my research. A mayor at the turn of the 20th century, he is known primarily for two things: Transforming Vienna into a modern city and being a virulent antisemite.

How antisemitic was he? So antisemitic that the Emperor Franz Josef I, who was friendly to the Jews, would not approve his election to mayor for two years. So antisemitic that Hitler cited him as an inspiration for his own views in Mein Kampf.

At least that’s how many historians view it. But the Encyclopedia Britannica, which I’d always considered a respectable source, sees it a bit differently:

Lueger, from a working-class family, studied law at the University of Vienna. Elected to the capital’s municipal council as a liberal in 1875, he soon became popular for his exposure of corruption. Though he was not himself a violent anti-Semite and regarded German nationalism with skeptical antipathy, Lueger did not hesitate to exploit the prevalent anti-Semitic and nationalistic currents in Vienna for his own demagogic purposes.

and

A believer in the equality of all nationalities in the multinational Habsburg monarchy, Lueger opposed Austro-Hungarian dualism and advocated a federal state. When the Christian Social Party won two-thirds of the seats in the Viennese municipal council in 1895, he was elected mayor; but the emperor, Francis Joseph I, regarding Lueger as a social revolutionary, refused to confirm his appointment for two years.

Emphasis mine.

So let me get this straight, Encyclopedia Britannica. Karl Lueger wasn’t really an antisemite — he only played one on TV because it was popular — or he was okay because he wasn’t a violent antisemite; he only incited violence with his rhetoric. And although he was an antisemite, he believed in the equality of all nationalities (except for Jews, who aren’t a nationality. Or a race. Or something). And the only reason that the imperialist emperor Franz Joseph didn’t confirm his appointment was because Lueger was a social revolutionary, not because he was a virulent antisemite who inspired racial hatred. Did I interpret that correctly?

It is noted by apologists that Lueger had many Jewish friends. Lueger’s cynical response to people who mentioned this to him is often attributed to Hitler: “I determine who is a Jew.”

Doktor-Karl-Lueger-Platz

So I was a bit shocked when, emerging from a central U-Bahn station, Stubentor, I saw a directional sign for Doktor-Karl-Lueger-Platz. Huh? Yup, close to the center of town, near the popular restaurant to which I was headed, Plachutta, is a plaza named for the man who inspired Hitler.

So I was a bit shocked when, emerging from a central U-Bahn station, Stubentor, I saw a directional sign for Doktor-Karl-Lueger-Platz. Huh? Yup, close to the center of town, near the popular restaurant to which I was headed, Plachutta, is a plaza named for the man who inspired Hitler.

The fallback rationale is always that he did so much for Vienna that he can be forgiven for this one flaw. Yes, and dictator Francisco Franco got the trains in Spain to run on time.  But wait, some will say. An important street in Vienna was stripped of its Karl Lueger-ness not long ago. This is true. According to an April 2012 article in The Guardian:

But wait, some will say. An important street in Vienna was stripped of its Karl Lueger-ness not long ago. This is true. According to an April 2012 article in The Guardian:

… 78 years after a portion of the main belt of boulevards that encircles the city centre was named the Karl Lueger Ring, the streets signs are getting a makeover.

Last week the coalition of social democrats and Greens running the Austrian capital decided to rename the 600-metre stretch of the Ringstrasse bearing Lueger’s name, triggering a row about whitewashing history, political correctness, and Vienna’s often difficult attempts to deal with a troubled past.

But as the article also points out, near the University of Vienna “a large statue of the mayor dubbed the founder of modern antisemitism still stands proudly. The city government said there were no plans to make any other changes.”

Here’s a picture of the statue that stands near the university.

[Note: Both of these photographs were taken by the author of the excellent post on Karl Lueger and Vienna in the Wanderlust für Wien blog.]

Where Is Herr-Professor-Sigmund-Freudplatz or Any Statue of Freud?

Which brings me to one of my favorite Viennese semites — outside of my family members, of course — Sigmund Freud. What about his legacy in Vienna?

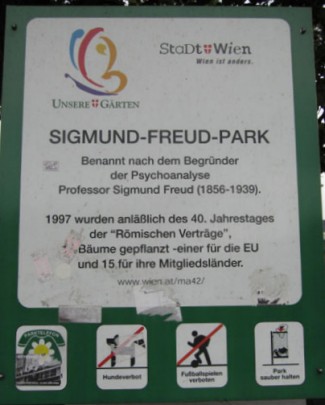

Amazingly, there is no street named for Sigmund Freud in Vienna, and no major plaza, just a park near the university better known for being backed up against the impressive Votive Church than for its association with Freud.

So… two grand, full-size statues of Karl Lueger, of whom almost no one outside Vienna or people doing research into the city has heard, and how many dedicated to Freud? None. Nada. Zilch.

There is a single bust of Freud in a “public” place, the University of Vienna. I found it–with the help of a guide–hiding behind some scaffolding in a row of undistinguished busts. Freud is not even in the center.

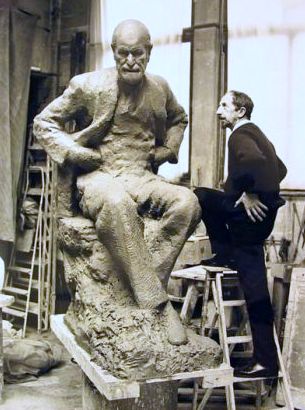

As it happens, a maquette of Freud by sculptor Oscar Nemon was commissioned in 1936 by the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society but it never materialized. A full sized version was, however, cast in London, where it stands in front of the Tavistock Clinic, a short distance from the Freud Museum, which has almost all of Freud’s belongings, including the bust made by Oscar Nemon of Freud in 1931.  Smaller versions of the statue exist in New York and Boston. Just not in Vienna.

Smaller versions of the statue exist in New York and Boston. Just not in Vienna.

Update, 2018: The Nemon Freud statue was installed at the University of Vienna Medical School in June 2018.

Very interesting. I would like to see a shorter version of this in the Forward. It answers an important question, about how you felt returning to Vienna, how tourists might feel, and then when you reflect further. I especially like your treatment of the Encylcopedia Britannica’s revisionist wording, and the value of knowing history when you look around in Europe..

That the bust of Freud was behind some scaffolding! that’s something really.

Thanks very much, Diane. As it happens, I will be doing a piece for The Forward about visiting Vienna’s Jewish Museum, which touches on the topic of my expectations of the city vs the reality.

Yes, I was looking around for a source other than Wikipedia to link to in order to explain who Karl Lueger was and was shocked to discover what the Encyclopedia Britannica listing said. As for the University of Vienna sculpture, there was a job fair going on, which made the Freud bust, not prominent to begin with, even more difficult to find.

Am loving your Tales from Vienna, Edie, with your unique voice and POV!

Why thank you, Laura! What a nice thing to say.

Really interesting. Vienna’s ambivalence about Freud, as I think I mentioned once, reminds me of Florence’s deeply conflicted attempts to capitalize touristically on native son Machiavelli – another personally respectable local genius with a “scandalous” world-wide rep. Of course, both are old cities with many famous sons whose reputations have morphed over the years.

I don’t recall your mentioning Machiavelli’s reputation in Italy vis a vis Freud — what an interesting comparison. It’s true — maybe in a few hundred years, Freud’s reputation might warrant a revisit in Vienna…

Fascinating! We can count on you to dig beneath the obvious to find the murky underbelly of history.

If ever a city–or an entire country–needed a session on the couch to integrate its conflicted feelings about the past—-

Murky is where I am happiest! And, yes, so true… Vienna could definitely use a bit of therapy!

Thank you for referring to my post on my blog Wanderlust für Wien as “excellent.” The reason there was no source for those particular photos is that I took them myself while I was studying abroad in Vienna.

Ah, thanks for this information — I thought the sources referred to the sources of the pictures! I would like to credit you for the photos; what form would you prefer?

The sources referred to some of the pictures, ones I did not take (such as the sign unveiling), but all the others were my own. You could just list them as taken by the author of the Wanderlust für Wien blog, if that would work.

Done — thanks!

Vienna? Anti-semitic? Heaven forfend the accusation!

Vienna may have recovered from its Cold War gloom, but as the French expression has it, “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Well, another thing that I heard was that, after Kurt Waldheim’s Nazi past was revealed, Austria began to air that discussion too. But there is still a long way to go…