In Part I of this series, I discussed Freud’s late life arrival at puppy love, including how my great uncle’s butcher shop provided meat for Yofi, Freud’s culturally Jewish — if not observant — chow. In Part II, I talked about the role the family dogs played in Anna and Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic practice.

Here I explore Freud’s final months in Vienna and the final year of his life in London — and a play set in the latter period.

A Dog Book Translation

A bit of background. Freud and his “Jewish science” were never in favor with Hitler — his books were burned in Berlin in 1933 — and in 1938, when the Nazis took over Austria, Freud’s life and that of his family were in danger. Freud was reluctant to leave, nevertheless, until his daughter, Anna, was held for a day by the Gestapo for questioning. After that, he was ready. It was not easy to leave Vienna by that time, however, and connections had to be called in.

In a review of Mark Edmundson’s The Death of Sigmund Freud: Fascism, Psychoanalysis and the Rise of Fundamentalism, John Gray writes:

No one could call Freud a sentimentalist. Yet he spent some of his last months translating, from French to German, a biography of a dog, a chow like Jofi, his devoted animal companion during his final illness.

The charge of sentimentality is a bit misleading. According to Freud biographer Ernest Jones (the one that Anna’s dog bit, as I mentioned in my last post), both Freud and Anna spent the difficult days waiting until they could leave Vienna by working together on a translation from the French of Princess Marie Bonaparte’s Topsy, Chow-Chow au Poile d’Or (Topsy: A Golden-Haired Chow). I’ve quoted from the introduction to the book several times in earlier posts; it’s the source of Ann Freud’s poem to Wolf. But it was Bonaparte who was responsible for getting Freud, Anna, and several other family members out of Vienna. Gratitude and the chance for a distraction — as well as their love for the chows — make this father and daughter project a natural.

That said, the tale of Topsy is revealing. According to Edmundson:

Freud adored this book and it was not only because of his affection for the princess and his love for chows, but also because of the story….Like Freud, Topsy has cancer: both are afflicted with tumors on the right sides of their mouths. Like Freud, Topsy has surgery, and is treated, as Freud will be, with roentgen rays and radium.

All turns out well. Topsy survives and thrives after her struggle with cancer, finding joy in her garden, in smelling the ocean… a nice dream of escapism for Freud whose circumstances are far more dire. As Edmundson says:

Freud, sitting with Anna in his study, going over their translation of the princess’s book, had the chance to think about recovery and even perhaps about resurrection, albeit indirectly. Freud and Anna together, telling the story of Topsy, could brood on the possibility of more life.

Yofi’s Death — and Her Successor

Freud’s struggle with mouth and jaw cancer — brought on by his addiction to cigars, which he could never quit — began in 1923 and, over the years, he underwent a series of painful surgeries. After a particularly difficult procedure, Freud wrote to Marie Bonaparte:

I wish you could have seen with me what sympathy Jofi shows me during these hellish days, as if she understood everything.

In January 1937, Yofi went into a veterinary hospital to have a pair of ovarian cysts removed. The surgery seemed successful, but three days after being released, Yofi died of a heart attack.

When his first chow, Lun-Yu, died, Freud waited 15 months before he could bear to bring another dog into his house. This time, Freud mourned deeply — he wrote “one cannot easily get over seven years of intimacy” — but brought another chow, Lün, into his home the next day.

Lün was Yofi’s sister, and there had been an earlier attempt to introduce her into the household, but Yofi wasn’t having it (can you say sibling rivalry?). Now Lün, who had been staying with the friend who raised her, returned to rule the household — and Freud’s heart. Thus the description of Yofi by Gray as Freud’s “devoted animal companion during his final [emphasis mine] illness” is inaccurate.

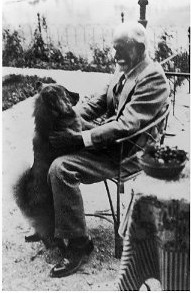

Freud and Lün in London

When Freud and Lün arrived in London on July 6, 1938, the dog was quarantined for six months. Her master went to visit her often, in spite of being 82 and ill. The press was charmed. “Nothing could have kept the great scientist away from his dog friend,” Michael Molnar, an Australian journalist, wrote. Further, Molnar quotes the kennel’s direct as saying:

I have never seen such happiness and understanding in an animal’s eyes…[Freud] played with her, talked to her, using all sorts of little terms of endearment, for fully an hour. And though the journey is long for a man of his years, he said that he was resolute about coming to see Lün as often as he can.

But Lün’s release from quarantine brought only temporary comfort to Freud, whose health was in rapid decline. By August 1939, Freud had a large open sore in his check and a rotting jawbone that created a terrible odor. Edmundson writes:

Lün… had always adored her master. Freud had petted her, walked her, and frequently, too, talked with her; she sometimes seemed to him the sanest presence in his life. But now she cowered on the far side of the sick room because of the smell of decomposition coming from her master.

A month later, lonely, too weak to read and in too much pain to talk very much — “My world is . . . a small island of pain floating on an ocean of indifference,” as he put it — Freud called upon a friend, Max Schur, to keep his promise to help ease him out of life when things got too bad. Schur administered large doses of morphine to him on three subsequent days. Freud died on September 23, 1939.

Freud’s Last Session — And Dog

I’ve mentioned that this series was adapted from one I wrote for my last blog, Will My Dog Hate Me. I discussed my disappointment in Lün, who had, I believed, abandoned Freud in his time of need. Whatever happened to unconditional love and loyalty?

At that point, I knew and thought far more about dogs than I did about Freud. But I subsequently went to New York and met with the director of Vienna’s Sigmund Freud Museum, where my great uncle’s butcher shop is now an art gallery. I also went to see the play Freud’s Last Session, based on a hypothetical meeting between Freud and C.S. Lewis in London during the final year of Freud’s life. A fascinating dialog between the famous man of faith and the famous atheist, the play seemed to get the details of Freud’s life right — except one.

In the beginning of the play, Freud calls out to an unseen barking dog, ”Come, Yofi.” But I knew — as you do now — that Yofi died when Freud was in Vienna; it was Lün who went along with the Freuds to London. In the play, Freud even mentions that his dog is avoiding him because of the smell of his jaw, necrotic from cancer, a detail I would not have expected the playwright to catch.

I noted this fact — and thus my surprise at the inaccuracy — on my blog. I suggested that maybe the playwright, Mark St. Germain, had made an artistic decision because yelling “Yofi” was far more mellifluous than yelling “Lün.”

Much to my surprise, I got a comment on the post from the playwright:

You’re right – I like the name “Yofi” better. He was, from what I read, Freud’s favorite dog.

Good eye, or ears!

Mark

I’m planning to write more about the play because my sense is that it captured Freud’s personality far better than David Cronenburg’s film about Freud and Karl Jung, “A Dangerous Method.” But I mention it now to say: a) How cool is it that the playwright responded? and b) How scary is it to know that, in the days of Google alerts, anyone you write about might be reading your work, even if it’s “only” on a dog blog.

Fabulous post in so many ways. Really. How cool is it that the playwright responded to your noticing his poetic license? What struck me most personally about your post is Freud saying about the death of Lun-Yu, “one cannot easily get over seven years of intimacy.” Exactly. Many of us form profound intimate attachments with our dogs. As any decent psychologist will tell you, broken attachments, regardless of the being (or thing, for that matter) with which they were formed, are very painful. I’d like to think that the good doctor would have taken seriously a patient deeply grieving the loss of her dog.

Thanks, Deborah. I wonder if any of Freud’s patients would have admitted to mourning the loss of a dog; I suspect Freud himself was surprised to discover the depth of his own feelings and his patients might have been embarrassed to admit them to the great man (hmmmm….something interesting to investigate!). I think it’s wonderful that he recognized it publicly and didn’t consider his mourning pathological. One of the things that I found most interesting was the difference in his reactions to the loss of his two dogs. The first time, he couldn’t bear to get another dog immediately; the second time he knew he needed canine company.

And, yes, I was bowled over by Mark St. Germain’s response to my post.

Wow, I don’t remember seeing the playwright’s comment but that is something I would brag about as well. I’ve often said that when we put things online, we have no way of knowing who is reading or how many lives we are reaching, even if we never see a single comment.

The play itself sounds quite fascinating. I read most of Lewis’ more overtly religious novels during an exploratory phase in university and I found him a very interesting person to study. I can only imagine what a conversation between he and Freud would have contained.

Kristine, the playwright’s comment was on another post, reporting on a trip I took to New York. Among the fun thing sabout revising these Freud and dog posts was that I could incorporate that information here. And yes, for better or for worse, you never know who’s reading!

I’m only familiar with Lewis’s work 2nd — or is that 3rd? — hand from plays like this and the movie with Debra Winger and Anthony Hopkins, Shadowlands, but it does sound fascinating.

This is moving in so many ways–the pain of Freud’s death, his abandonment by his animal companion, the sheer difficulty of his last couple of years, in which his very special status did not protect him from being driven out of Vienna.

I read C.S. Lewis’s powerful Narnia books (starting with The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe) when I was a child, quite unaware of the Christian theology that inspired them (the lion being the Christ figure, etc.). I’m glad my non-believing parents (who, by the way, were of the generation fascinated by Freud’s radical theories) did not say anything to break the spell.

There’s a saying that animals make us human and that’s what I felt about Freud when I researched his relationship with dogs. I never did read any C.S. Lewis when I was a child (or later) though I doubt it was because my parents were trying to keep me from the theology; I wasn’t aware of other classics like Winnie the Pooh either. But all this is jarring a memory of a fairy tale book — Grimm’s? — in German that my mother simultaneously translated while reading to me.

I’m waiting to read your biography of Frankie (as told to…, or, more accurately, as barked to….)

Talk about difficult translation projects!

Hi Y’all!

Just hoppin’ by to say “hi”.

Y’all come by now,

Hawk aka BrownDog

Thanks for coming by, Hawk! I’ll stop by and see you right now.

I’m late swinging by, but I wanted to tell you that I really enjoyed this series of posts!

Never too late — thank you!

Neat blog! Is your theme custom made or did you

download it from somewhere? A design like yours with a few simple tweeks would

really make my blog shine. Please let me know where you got your design.

Thanks a lot

If you email me through the contact form I’ll be happy to let you know.

Great job on the series exploring the role of dogs in Freud’s life and psychoanalytic practice! Your latest post about Freud’s final months and his translation of Topsy was particularly intriguing. It’s fascinating to learn about how the book gave Freud a chance to think about recovery and more life. Your writing style makes the historical background and details easily digestible, and the way you tie in quotes and anecdotes from other sources adds depth to the narrative. Overall, a fantastic read!

Thank you for reading — and for your kind words about my writing! I’m glad you enjoyed the series. It was fun for me to research and write!