Foie gras has always been a guilty pleasure. It’s ridiculously expensive, it’s fattening… and then there’s the whole animal cruelty question (which I’ve discussed a bit here). So I’m not sure whether my discovery that it is a traditional Jewish food makes me feel more or less guilty about it.

My journey of goose liver discovery started with Jane Ziegelman’s excellent 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement. I bought it at Manhattan’s Tenement Museum because I thought it might shed light on the practices of butcher shops in Europe, as translated to America. It didn’t, at least not directly, but it illuminated Jewish animal husbandry practices that are definitely relevant. And it’s a great book about culinary history.

Fat Was a Problem For Ashkenazi Jews

I’m not talking about being a little zaftdig.

The Jews of Spain and the rest of the Iberian peninsula, the Sephardic Jews, used olive oil for cooking; it was pareve (neither milk nor meat) so it could be used for any type of dish. In contrast, the Askenazi Jews of northeastern Europe had a problem finding fat to prepare meat dishes. Pigs were off limits; so was beef tallow (I’m still a little unclear as to whether it was forbidden because it was set aside as for ritual purposes, according to Leviticus, because it is from a nonkosher part of the cow).

The Ashkenazi turned to poultry fat, commonly called schmaltz. Until I started reading up on this topic, I thought schmaltz only referred to chicken fat. Apparently it’s a more loosey goosey term: It turns out that, for centuries, geese were the premier schmaltz sources.

As Ziegelman puts it:

As early as the eleventh century and possibly before, German Jews had taken up goose farming, raising birds that were stunningly plump, veritable fountains of fat. Their secret was force feeding. A month or so before slaughter, they were subjected to a rigorous feeding regimen in which compacted pellets of grain or dough were pushed down the animal’s throat (p. 112).

Saying “Eat, eat,” was not enough?

This practice was controversial among Jewish authorities from the start. According to an article on geese in the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe:

Rashi (1040–1105) condemned force-feeding on the grounds that it caused the goose pain; Mosheh Isserles, whose annotated version of the Shulḥan ‘arukh appeared in Kraków in the sixteenth century, took a lenient position on this question.

Eat Your Foie Gras, It’s Good For You

If goose fat was the primary goal of the geese fattening, another organ provided a side benefit. Ziegelman says:

If goose fat was the primary goal of the geese fattening, another organ provided a side benefit. Ziegelman says:

The bird’s enlarged liver… was roasted and dutifully fed to the children as a nutritional supplement, the same way American children were given doses of castor oil (p. 113).

But not all Jewish mothers relegated goose liver to medicinal roles. Jews were considered crucial to a gourmet industry usually associated with the French. From the Artisan Farmers history of foie gras:

The ancient Egyptians hunted and then domesticated geese, and discovered that waterfowl developed large, fatty livers after eating large amounts in preparation for migration. To replicate this naturally occurring large liver, the Egyptians, over 4000 years ago, developed the technique now known as gavage to produce a fattier bird. The practice of gavage spread throughout the Mediterranean, and was adopted by the Greeks and then the Romans, the latter of whom made foie gras into a delicacy in its own right.

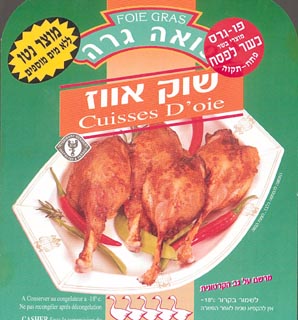

After the fall of Rome, and during the medieval period, it was the Jewish population who kept the tradition of foie gras alive. Goose meat served as an excellent source of nutrition and the animal also provided cooking fat that conformed to Jewish law. Wherever Jews moved across Europe during the Middle Ages, they brought with them the tradition of goose fattening.

This explains why Israel was one of the world’s largest producers of foie gras– until its production was banned in 2006 because of the Jewish injunction against animal cruelty. (Interesting fodder for another post: Did the practice of gavage become crueler, or did modern Jews grow a conscience that their agricultural forebears couldn’t afford?)

The YIVO geese article notes:

Foie gras was the pinnacle of luxury and especially favored by Hungarian Jews. Hungarian Jewish specialties from the nineteenth century include a whole foie gras cooked and preserved in goose fat, as well as fried slices of foie gras topped with a mixture of hardboiled eggs, grivn, goose fat, and minced onion, and sprinkled with paprika.

I’ll have a Diet Coke with that.

You say gribenes, I say grammel

The word “grivn” in the previous paragraph refers to grieven or gribenes, the Jewish version of pork rinds; it’s the crispy by-product of rendering chicken fat into schmaltz and adding onions. I never experienced gribenes in my home — or so I thought. My mother used to make what she called grammel, which turns out to be the Austrian term for this specialty.

Only in Austria it’s usually made with pork. And in my mother’s house no fat rendering — or onions — were involved. She simply took chicken skin and put it into a pan until it was crispy, discarding the oil. It was therefore less fattening than eating chicken skin — and even more delicious.

Maybe it’s the snob in me; maybe it’s primal, a return to my family’s agricultural roots. I’ll pass on the gribenes and traditionally-made grammel and go for the foie gras — especially now that I know it’s health food.

Interesting stories, and I definitely did not know all this . . . except the part about force-feeding the goose. Today everyone is so occupied with asking the question, What type of fat is it? Omega-this and omega-that. I do recall that as a child I loved the taste of beef fat at the edges of a T-bone steak. And in The Odyssey, the best cuts of meat have plenty of fat . . . probably a question of storing calories for survival. And I love that crispy Peking duck in Chinese restaurants.

However, my main attitude toward fat has become intimidation. How solid does the fat get at room temperature? If somewhat or very solid, then I’m afraid I fear for my arteries. I’ve become an olive oil gal.

Enjoyed your stories, though!

You can go crazy with the latest on food/health trends. Last night I watched Michael Pollan say that it doesn’t matter what you eat; all that counts is how it’s cooked. I’m an omnivore but I try — emphasis on try — for moderation in all things. And I go to the gym as often as I can drag myself there.