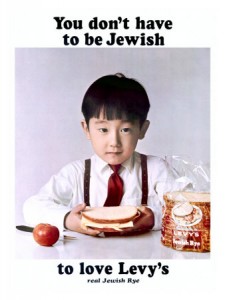

As I mentioned last week, one of the ten genealogical questions I want answers to — #2 to be precise — was researched by a good friend, who became very interested in the history of my mother’s family, the Kornmehls. The result was this wonderfully rich guest post. Blame — or thank — me for the illustrations. I came across this classic ad as I was searching for a picture of Jewish rye bread and couldn’t resist.

***

by Lydia Davis

Family Names

When you’re searching for ancestors, or living family, it helps if the family has an unusual name.

I found a lost first cousin of mine because her name was so unusual–both first and last–that when I resorted to Facebook in my search for her, she immediately and unmistakeably popped up. She may well be the only person in the world with that name. Now she and I are in touch, she has discovered some half-siblings, and she has a readymade set of first cousins, as well as an album of family photos and a collection of family stories that she never had before. (Her father did not stick around past her infancy; she never met him.)

But if your last name is Davis, for instance, or Jones, or Stein, it’s much more difficult.

The Kornmehl Family

Kornmehl is not a common name. As one of Edie’s new-found cousins said, if your name is Kornmehl, you know you are related to all other Kornmehls. That is very unusual, and there is something very satisfying about that finite cast of characters, with its many possibilities of discovery. It also inspires the genealogically-minded to try and track down every single Kornmehl. Fortunately, not everyone is bitten by the bug; just a few in every family are willing to spend hours poring over the spidery writing in old records or Googling names to pin down the facts.

I’m not a Kornmehl, but I seem to be one of those genealogico-philiacs hopelessly infatuated with the detective work involved in tracing family lines and the excitement of making connections–even if it’s not my own family. I will stay up until the wee hours of the morning poring over old telephone books. Fresh from my own, more mundane, family research (though of course no family history is completely mundane), I’m fascinated by the dramatic and moving history of the Kornmehls through the centuries and all over the globe.

The Name

About the name–at first I naturally jumped to the most obvious conclusion, that it meant “cornmeal.” There are so many cognates between German and English–Old High German being, of course, one of the sources of our language: vater, father; mutter, mother; bruder, brother; Hund, hound; Katz, cat; Milch, milk; etc. Obviously the German Korn and our “corn” are related, as are Mehl and “meal.” But as usual with language, it is more complicated. It turns out they are “false friends”–but it also turns out that this has something to do with the evolution of the American word “corn.”

I looked up Kornmehl the lazy way, by Googling, rather than getting a German-English dictionary off the shelf. I found “wheat meal” and “grain meal”–no corn. I thought of the fact that in the British Isles, “corn” is used to mean whatever grain is grown in a particular region. (As far as I know, they still can’t buy a good, fresh version of what we in America call corn on the cob.)

In any case, to get back to the name, now I assumed “kornmehl” was probably “wheat meal” or “grain meal.”

Then, recently, I Googled “kornmehl” and came upon a cooking chatroom in German. The discussion was about baking. One woman had posted a comment about the word “Kornmehl” (nouns are always capitalized in German, which helps in deciphering a sentence). It opened my eyes to another possibility.

This is what she said:

Korn- und Roggenmehl sind das selbe. Kornmehl (‘K e u n m ä h’ höre ich meine Omi sagen…) ist nur ein älterer, bei uns in der Gegend früher gebrauchter Name für Roggenmehl.

Translation:

Korn- and Roggenmehl are the same. Kornmehl (‘Koin-meh,’ I hear my grandma saying…) is only an older, earlier name used for rye flour in our region in the past.

(The German formulation actually involves one of those unwieldy adjectival phrases: “an older, in-our-region-earlier-used name for rye-flour.”)

It would be nice to know what her region was, and how old her grandma would have been… But when I read this, I thought we could safely assume–since things changed more slowly in the past–that “Kornmehl” also meant “rye-meal” back in the days when the Kornmehl family adopted their name, and that more than one old woman in a German-speaking or maybe Yiddish-speaking region shuffled around calling it, not “korn-mayl,” but “koin-meh.”

Then I came upon a confirmation of the meaning in a U.S. Congressional report dated 1910, which located the word geographically and corrected “meal” to “flour”:

The Austrian mills use almost entirely home-grown rye and wheat. In years of exceptionally high prices rye is imported from Russia or Roumania…. Durum wheat is apparently unknown in bakeries here. The flour produced here from rye is called in German “kornmehl,” but it has nothing in common with our corn meal, as it is made exclusively from rye, which is one of the biggest crops in the country.

Now I consulted a German-English dictionary and I see: the first meaning of Korn is actually any kind of grain, including a grain of salt or a grain of sand. But the second meaning is “rye”– because rye was such an important grain. Our U.S. word “corn,” for the sweet yellow niblets, is actually the word that has strayed from the original meaning, and it is the British sense of “corn” that is more true to the original. (Soon after, I found a nice example of that British usage in the first pages of Dickens’s Oliver Twist: “[to feed the poor,] they contracted…with a corn-factor to supply periodically small quantities of oatmeal.”)

The Choice

So that question seems answered for the moment, though another question still remains: why did the Kornmehl family choose that name? It was presumably taken at the time when Jews were required to adopt permanent German surnames. Before that, they had gone by traditional Hebrew last names consisting of “ben” (“son of”) and the father’s Hebrew name.

Here is Wikipedia on the history of Jewish surnames:

The process of assigning permanent surnames to Jewish families (most of which are still used to this day) began in Austria-Hungary. On 23 July 1787, five years after the Edict of Tolerance–in which Joseph II granted religious freedom to Jews–the Austrian emperor Joseph the Second issued a decree called Das Patent über die Judennamen which compelled the Jews to adopt German surnames.

Prussia followed suit, district by district, up to 1845.

According to Helen Epstein in her wonderfully engrossing Where She Came From: A Daughter’s Search for Her Mother’s History, under this law, if Jews were willing to pay, they could choose a pretty name, or a name based on vocation, or one describing their place of origin. If they did not pay, they were stuck with whatever the authorities chose to give them. (Then again, she says, there were those who simply rebelled and stuck to their Hebrew names.)

In the 18th century, as the Kornmehl family genealogists have established, at least some of the family were millers and traders in grains. But I still feel there’s a missing link: It makes sense to call yourself Miller if you are a miller, but if you milled or traded in rye flour, would you call yourself Rye Flour? (If your business were the manufacture of radios, would you call yourself Radio?) I would like to know more about how families named themselves when the field was wide open to them (so to speak).

Bio: Lydia Davis is a writer of short fiction and a translator, mainly from the French but more recently from the Dutch (the very short stories of A.L. Snijders). Her latest publications are a Collected Stories, a new translation of Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and a chapbook called The Cows, about her neighbors across the road where she lives in upstate New York.

This is absolutely fascinating. My husband’s name, Badertscher, is one of those that you-can-bet-anyone-with-the-name-is-related names. Therefore seeking his family routes has been pretty easy. However, my family name Kaser has so many variant spellings–and so many ancestors named Joseph, that I haven’t gotten far with it.

It had not occurred to me to try to look at how far back the adoption of surnames went. Love your thorough research.

I didn’t know your family name was Kaser — interesting. Have you gotten to the point of knowing anything about the derivation, e.g., a relationship to Kaiser?

I will let Lydia thank you — if she likes — for the compliment about the thorough research.

Thank you, Vera–though I feel I’ve barely scratched the surface in researching the fascinating history of surnames. I’m beginning to think that the more puzzling ones may well all have been bestowed by government administrators… I wonder what your husband’s name means? It sounds like an “occupation” surname, but I haven’t looked it up. Meanwhile, I look forward to reading your own post!

By the way (more on surnames), I was amused to notice at a certain point a few years ago how my husband and I tend to create surnames quite spontaneously, which gave me a clue as to how some of them came into being more naturally than by Austro-Hungarian edict: we would not refer to “Sharon Smith,” since we weren’t that familiar with her actual surname. We would say “Sharon-from-the-library” or “Sharon-with-the-red-hair.” I think we all do this without realizing that we’re creating surnames.

Korn in German can also mean kernel. That would account for its more generic usage in baking. Could acorn in English also refer to a kernel, I wonder?

Interesting — and, yes, that would make sense, wouldn’t it? Thanks for coming by and commenting. I’m very much looking forward to your longer contributions to this blog.

Hi, Christine. Thanks for commenting. Your reply has sent me back to the dictionary (which is never far away!). I’m glad you brought up “kernel,” which is related: it is derived from the Old English “cyrnel,” a diminutive of “corn”–in other words, “little corn.” “Acorn” is trickier–my instinct would say it must be related, but in the first source I’m checking, we only get as far back as a derivation from the Middle High German “ackeran,” meaning “acorns, collectively.” Now that you’ve led me to the pleasant image of a crowd of acorns, I’ll do some more research and report back if I find anything new.

Surely Alexander Beider (Dictionary of Jewish Surnames; Galicia) would shed light on the surname?