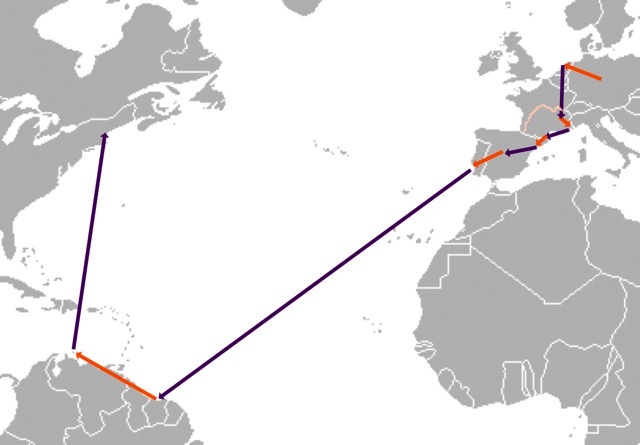

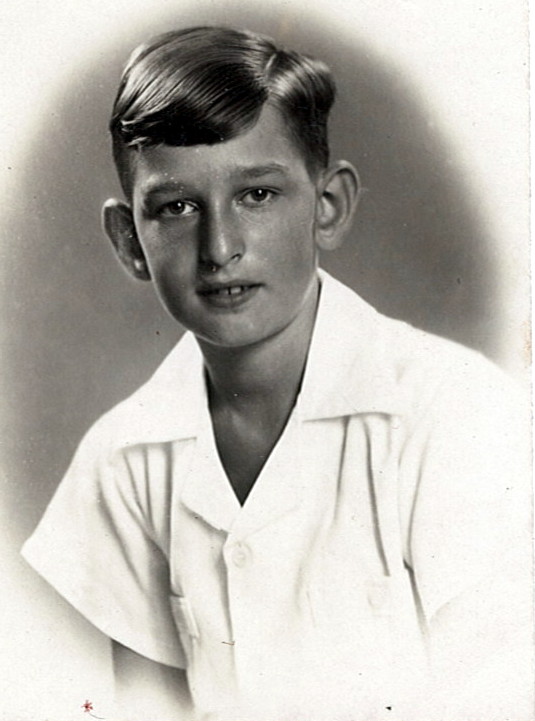

Last July, when I posted an excerpt from Manfred Wolf’s memoir, Survival in Paradise, I was pleased — though not at all surprised — by the positive response it got. It’s a very moving piece about a young boy’s coming of age during World War II. So I am doubly pleased to have gotten permission to post another excerpt from the book, this one from Chapter 12, when the Wolf/Kornmehl family finds itself after the war in Curaçao, where they fled from Europe. It is 1948, and the State of Israel has just come into being.

Survival in Paradise:Curaçao

by Manfred Wolf

During the late forties, in the beginning of the Cold War, my father was once again making escape plans. “You need a country to jump to, if you have to. You just can’t rely on any place remaining good.”

Much to my regret, my parents were reluctant to return to Europe. Life in Curaçao was temporary, of course, but Europe seemed too dangerous with another world war almost inevitable between the U.S. and Russia. Ever since we fled Holland, I wanted to return there and resume the life the war had stopped.

Before the war, in 1940 in Holland, we had a visa for Bolivia and Peru, but my father hesitated. “What will we do there?” I was five years old, but he showed me both Peru and Bolivia on the wall map of our dining room in Bilthoven, then checked the annual rainfall in an atlas and was appalled by how dry it was. He continued to worry about the wisdom of this move, mulling it over, but when the Germans invaded Holland in May of 1940, it was too late to go anywhere and we were trapped. Never again would he make this mistake. And never again would he feel secure. The war had proved that all security was an illusion. Now, after the war, there was still no reason for complacency. “You’ve got to have a country in reserve.”

***

The celebrations in our Jewish Club about the birth of the State of Israel were muted. Everywhere danger threatened the new state. Arab armies invaded from the north, the east, the south. It was not clear that the Jewish state would be able to survive.

“The danger,” I lectured my teacher Mr. Gos at school, “is that the Egyptian army and the Jordanian armies will join together, say, in Be’er Sheba or elsewhere in the Negev desert.”

Mr. Gos beamed at me; his bald head shone in the sun. “You really know about this, don’t you?”

“Well, yes,” I replied.

“And you take it to heart?”

“Of course.”

“But don’t worry too much. Next week is another school trip to Bonaire, and I want you to enjoy it.”

He had such an air of quiet, that man, such contentment, like so many Dutch people.

A few weeks after our celebration, it seemed clear that the Jews — or the Israelis, as we now called them — would win the battle of Palestine. One of my Jewish classmates talked about moving there and got all excited about all the planes they would have to take to make the trip. “We’ll fly via Bermuda,” she said.

“Wouldn’t you rather move to Holland?” I asked.

“No, we’re going back to our ancestral home.”

At the Jewish Club, a young woman from the Israeli Army, Yael, gave a fiery speech in rapid English. Her “R”s were Germanic, or was that a Hebrew accent? I didn’t listen to what she said because she cut so striking a figure in her military garb, half soldier, half Campfire girl. When it was all over, some of the Club members sang “Hatikvah,” the new national anthem.

“What did you think of this Yael?” asked my mother with just a hint of disapproval in her voice. She patted the hair on top of her head while she spoke.

“I don’t know,” answered my father slowly, distantly. “She’s strong, like a goy.”

“Well, yes,” said my mother, sounding unconvinced.

“Was she really in the army?” I asked.

“In the Haganah,” my father said proudly. “The army that defeated five Arab armies. How is it possible?”

“Women fight next to men,” said my mother. “They wear a uniform. They handle weapons. They can defend themselves and go on the attack. If only…”

“These Jews are different from the way we were,” my father answered her. “What could we do? Who had a weapon in Europe? Who could even use one? We were scared, frightened beyond belief. Yes, maybe the Partisans fought in the woods, but most of us…”

“Sometimes I think,” said my mother, “that we all went too quietly.”

“But Bertha, where would we even have found guns? Where could we go? We fled in the night. And lucky we were. The rest were taken.”

“But back to this Yael,” said my mother. “Why does she have to wear shorts? Here in Curaçao where everybody is decently dressed, even the Curaçaoans.”

“Especially the Curaçaoans,” I interjected.

My mother laughed a hearty, gratifying laugh. “You’re right. Curaçaoans have a real flair for clothes. You never see them disheveled. Even when they’re poor.”

“Sometimes the Dutch look sloppy,” I said, encouraged by her agreement. “But they don’t care. You have to give them that.”

“All true,” said my mother, “but shorts? Who wears shorts around here? Yes, on the beach.”

I had liked Yael in her shorts but couldn’t help agreeing with my mother. Didn’t she know that everyone stared at her legs? Every time I had seen her, she had worn the same outfit: khaki shirt, very military, long-sleeved, but her shorts were provocative, seductive.

Days later, Yael walked into our store. She wore a skirt and a kind of halter top, as if she now decided to switch the area of attention. A bare midriff was rarely seen in the downtown streets of our Caribbean town.

“Shalom, shalom.” Since we spoke no Hebrew and she no Yiddish or Dutch, the conversation continued in English and German. Yael was troubled by something; she was frowning and looked annoyed. “These Curaçaoan Jews give generously to the cause. But it’s clear they don’t understand anything,” she sighed bitterly. “What nonsense they talk. ‘You beat the Arabs,’ they say. ‘Here, here, take a thousand guilders. Now go away.’ They think beating the Arabs is a one-time, simple thing. They don’t know; they don’t want to know.”

My father looked up. “One time? You mean this fighting will go on and on?”

“Of course,” said Yael sternly, and took a cigarette from a small case in her shoulder bag, which raised her halter top a bit and revealed the little curved rims of her tanned breasts. “It’s not just the Arab armies; it’s the people who had to leave their homes.”

“Can’t they go to Egypt and TransJordan?” I asked.

“Yes, of course. They can go there. But do they want to go there? Or will they come back as fighters, guerrillas, assassins? We cannot let our guard down for a second.”

“Here I thought we won,” said my father, “but now …”

“Well, we did win,” said Yael, puffing furiously on her cigarette, her sunburned face stiff and scowling. “We did. We won the war. We can’t be victims anymore.”

“No,” said my mother. “Never.”

“We will never run away again.”

“I hope not,” said my father dubiously.

“Now it’s someone else’s turn,” continued Yael. “Besides, if you have a conscience, it will be held against you.” She unstiffened as she said this.

“But tell me, Yael,” asked my mother, “Are you a Sabra? Where were you born? Judging by the way you speak German, your parents were German Jews.”

“My parents. I rarely speak of my parents. But when you told me the other day, Herr Wolf, I mean Max, that you lived in Chemnitz, I decided I wanted to tell you the whole story.”

“You mean you come from Chemnitz too?” asked my father, his brown oval face held attentively to one side. My mother looked speechless.

“My name may be Yael Yadin, but that is just the Hebrew version. I was born Hettie Springer.”

My father sighed. “I knew a Springer once. He helped me get started in business. In Chemnitz. But he is dead now.”

“Just so. That was my uncle.”

“Your uncle,” exclaimed my mother. “We heard that he and his wife and the children had all died.”

“As have my parents and sisters. I am the only one,” said Yael, now quickly turning her face away. I did not want to see her cry, so I turned away too. Why did it always come to this? Why did everything always turn to sadness? “In 1936, three years after Hitler came to power, my family had a chance to go to Palestine. Everybody said ‘Don’t go. It’s too dangerous. The Arabs will kill you. Europe is still best for us. Especially Germany. Germany will not hurt its Jews, the way Poland has.’ My father said so too, but he had modern, democratic leanings. We took a family vote. And the vote was four to one against leaving Germany.”

Everyone was quiet now. I looked at her stern, thin-lipped face and beautiful upright posture. A few droplets of sweat clung to her light-brown middle. Finally my father said: “A vote? Four to one? Your sisters, what were their names?”

Yael did not answer. Instead she said, “They were good girls, good students, never in trouble. I always was.”

“How old were you?” asked my mother, obviously trying hard to remember the girls.

“I was sixteen and a bad girl. I was probably the only Jewish child in Chemnitz who dropped out of school. My parents could do nothing with me, nothing. Once or twice I ran away from home too. I played in a cabaret. They thought I would become a prostitute. Well, they weren’t so far off.”

“So then you set off for Palestine.”

“Yes,” said Yael, “I was not much older than Manny is now.”

But of course she was. “I’m thirteen,” I said.

“Yes, but you are big for your age.” And Yael gave me a wide-mouthed smile, which made her look younger than twenty-eight.

My heart gave a jump, but my father pursued the conversation: “So how is it in Israel? Is it really Jewish? Are the police Jewish?”

“We have Jewish everything. Jewish police. Criminals. Even car thieves.”

“Incredible,” said my father. “Jewish car thieves.”

“Well,” said Yael, “I have to go. Two other Israelis are taking me out for peanut chicken and funchi.”

“What’s that?” asked my mother.

“It’s cornmeal,” I explained proudly. “Curaçaoans eat it a lot.”

“Cornmeal,” said my father flatly but with a glimmer of recognition.

“Don’t you people eat the local food?” Yael asked scornfully.

“No, we eat European food.”

Yael shrugged and rapidly said good-bye. “The Soviets were ahead of us all,” said my father abruptly. “They created a Jewish national homeland in Birobidjan.”

“Isn’t that in Siberia?” teased my mother.

“Yes, but a good part of Siberia, a wholesome part, in the Far East. There Jews can live together and speak Yiddish. They drained the swamps and cut down the forest. I read about it in my socialist paper.”

“Well, we now have Israel,” sighed my mother. “That’s obviously better than Siberia. In Haifa,” she continued, “there are lots of European Jews. They came there in the thirties and speak German at home.”

“Real Germans,” smiled my father. “I’ll bet they’ll never learn Hebrew.”

“Still, it may be a place for us some day.”

“Yes,” answered my father pensively. “You never know, maybe we’ll have to go there someday.”

“If we went to Israel,” I said, “we wouldn’t need to look for any more countries.” I had never seriously thought of going there before.

“How can we be sure?” asked my father.

©Copyright Manfred Wolf, 2014

I found this wonderfully written and profoundly moving! It created such a sharp impression of time and place with a minimum of words. Each person was so vividly etched. It contained melancholy and humor… beautifully done. Can’t wait to read the entire book.

Hope it achieves a very wide readership!

Our family path to survival never ceases to amaze me! Manfred’s family’s trek through Europe to Curacao pays tribute to the will to survive and the willingness to adapt to new lives in far away places. It is a common thread through the Kornmehl family. They were dispersed to distant corners of the world and the branches were separated for so many years. Now, through family endeavors like Freud’s Butcher and the family book anthology, they are being reunited.

This is such a marvelous combination of memoir and history. Yael appears through the admiring gaze of the writer who, not entirely distracted by her feminine appeal, records her views that seem prescient. She’s a Cassandra figure I won’t soon forget. Nor will I forget the poor teacher, confronted with a student, intelligent beyond his years, determined to make him forget his worries and just enjoy the field trip. These details elevate the author’s narrative far above other memoirs I have read.

Manfred has given us a taste of his memoirs. Both gripping and painful, the excerpts convey his family’s courage, hope and survival during an ugly time in history. For anyone who has read “Almost a Foreign Country,” Manfred remains true to his masterful style, combining elements of fear, romance, brutality, compassion and adventure.

I am eagerly anticipating the publication of his memoirs (or additional excerpts if he decides to post). The memoirs will make compelling reading, providing a testimony to resourceful, bright children who can cope, adapt and survive when forced into extreme conditions.

I loved your story, and would love to hear more memoirs of that time.

Of course I knew of your family connection with Curacao and it was interesting to read about it…. I remember your mother and grandmother.

I started trying to find out some more about my father and what his background was on his Steuer side, and came up with nothing. I miss him so much and wish I could have had more pictures and more information but there is nothing of his history other than the time he lived in Chemnitz and Tarnow with the Kornmehls,. Nothing at all about his father’s side, though I believe there was a Kornmehl connection there too.

Sandi

there has been no reply to my comment on your story….. I am hurt that I was pushed off the site by Jill Kornmehl.

S. Steuer

Again, I’m not sure what you mean but Jill has nothing to do with this site’s administration.