UPDATE: I was wrong.

I hate that — especially since it means the mystery of Erika remains unresolved.

What happened?

Sometimes I think that if I wait long enough, relatives will turn up to resolve all my genealogical issues — or at least clarify them.

The original post, below, posited that two childless members of the Kornmehl family, the Schweitzers, tried to save the life of a niece, Erika Allina, by claiming her as their daughter.

But since I wrote this post, I was contacted by one of Curt Allina’s daughters (from his second marriage) who had — what else? — found this blog because she came across my posts about her father, the Man Who Put the Heads on Pez. After a few back and forths, she sent me an unpublished manuscript of a short memoir that her father wrote.

There were many revelations, some fun — for example, that OSK’s beard (see picture, below) is blond; for some reason, I always thought it was grey — many more difficult. Curt’s was a tragic tale. What is relevant here is that I had thought that Curt and his family (including sister Erika) had grown up in Prague and moved to Vienna after their scoundrel of a father ran off to the U.S. Turns out I had gotten the sequence of events exactly backwards: The children all grew up in Vienna and moved to Prague when they were still young, making it unlikely that the Viennese Schweitzers could plausibly have laid claim to a girl living in another city as their daughter.

I realize this is all too convoluted for most people to follow. The most relevant takeaways:

Genealogical finds result in a constant re-writing of history, an endless revising of theories about your relatives.

Shorter: Genealogy means always having to say you’re sorry.

***

I left February’s Family History Writing Challenge with several unsolved mysteries relating to my great uncle and aunt Adolph and Bertha Schweizer. The one that was the most puzzling, however, was the appearance on Adolph’s exit application of a daughter named Erika, born in 1925. Bertha would have been in her 50s in 1925, too old to bear children. I assumed Erika was adopted, but I couldn’t find any records to confirm this. Nor could I find anything about the fate of Erika Schweitzer in the Holocaust databases.

Now I’m going to hazard a guess: I think Erika Schweizer might have been Erika Allina, niece of the Other Siegmund Kornmehl (OSK) — the one who owned the Cafe Victoria, not his brother-in law who had a butcher shop in Freud’s building. (And yes, having two men in the same immediate family with the same name is the definition of genealogy hell.)

Here’s why.

OSK’s Family

The story begins with Aron Juda Kornmehl, born in Tarnow, Poland, in 1852. In 1876, Aron married Rivka (Regina) Spiegel. They had three children, Siegmund (b. 1875), Helena (b. 1887), and Mina (b. 1894).

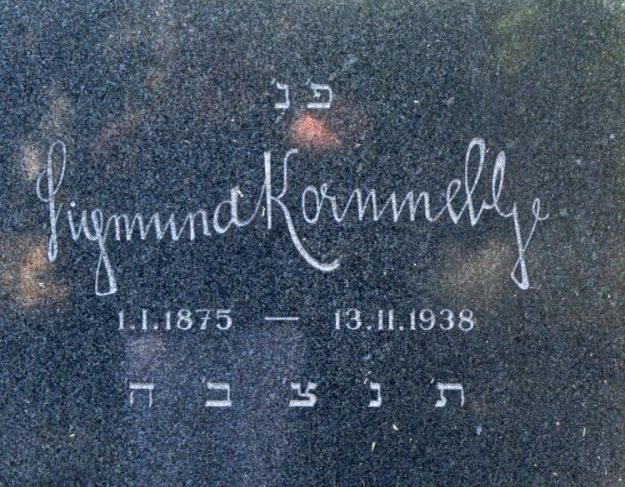

In 1899, Siegmund married Anna (Chana Jente) Kornmehl, born 1877. She was his first cousin — which explains why they were both named Kornmehl. Siegmund died in 1938. Precisely when in the year is key to this story.

Anna and Siegmund had four children: Alfons (b. 1899), Margit (Greta, b. 1913), Egon (b. 1901) and Henriette (Hetty, b. 1908), all born in Vienna.

In 1917, Mina married Ervin Allina, who was originally from Czechoslovakia. They moved from Vienna to Prague to be near Ervin’s family. Ervin and Mina also had four children: Gertrude (b. 1918), Hans (Jan, b. 1919), Curtis (Curt, b. 1922) and Erika (b. 1924). Not long after Erika’s birth, Ervin left his family behind in Prague and hightailed it to America. When it became clear that her husband wasn’t coming back, Mina moved with her children to Vienna to be closer to her brother Siegmund and his family. They lived on 18 Berggasse — a notable address, and not only because it’s next to Freud’s home. In addition to the main butcher shop at #19 Berggasse, the original Siegmund Kornmehl had a smaller kosher butcher store at #18 Berggasse, and presumably owned the building since it’s where the Allina family lived. According to the Shoah testimony of son Curt Allina, his mother took in boarders, mostly college students, to make extra money.

The Tale of the Tombstone

I’ve written about my rather woo-woo experience at the gravesite of OSK, which I was led to by a deer. Less woo-woo — and more relevant to this story — are the birth and death dates engraved on OSK’s tombstone.

At first glance — and second and third — I was certain that Siegmund died on 13 November, 1938. In fact, I found that date rather disconcerting because it was right after Kristallnacht, November 10 and 11. This suggested to me that perhaps OSK had been beaten or died of a heart attack as a result of these horrendous events.

Time passed. The Family History Challenge — and, more recently, my upcoming talk in Vienna on October 4 — reminded me that I’d been remiss about adding information to my family tree on Geni.com. When I went there to add the information from the grave marker, however, I noticed that there was already a death date listed for OSK: 13 February, 1938.

That’s when I looked at the gravestone more closely.

If those second numbers, representing months, were Roman rather than Arabic numerals, that would make the Geni.com date correct. And the numerals in the month do look slightly different than those in the date slot. But mixed Roman and Arabic numerals on gravestones? I’d never heard of that. Posing the question on a Jewish genealogy group on Facebook got me soundly mocked.

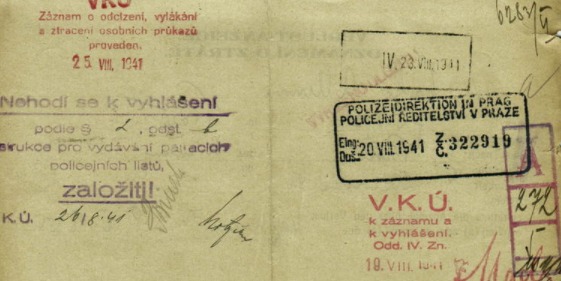

Then I found this exit visa:

Whose it is and what it represents isn’t relevant here. The point is that it’s an official document in the Austro-Hungarian empire that mixes Roman and Arabic numerals in the same way that OSK’s gravestone does. So the death date already listed on Geni.com was correct.

A hypothesis

Imagine this, then. It is late 1938. OSK has died earlier in the year, leaving Anna with four fatherless children. Her sister-in-law Minna also has four fatherless children. But Anna’s sister, Bertha, and her husband, Adolph, have no offspring. No Jews are safe in Vienna by this point, the anti-Semitic strictures following the Anschluss having moved rapidly, but Bertha wants to try to save her sister’s youngest niece, Erika. She and Adolph decide to puts Erika’s name on their exit application.

Sadly, the attempt wasn’t successful. The Schweizers were deported to Treblinka, where they died in 1942; Erika Allina died in Lodz in 1941. The document above is her stamped exit papers.

The only glitch to the story is that on the emigration form, Adolph Schweitzer says Erika was born October 25, 1925. Erika Allina’s records show she was born May 17, 1924.

This seems to me like a quibble. The birth dates are different, but if you are trying to pass a more distant relative off as your child, why not give the girl a slightly different (but in the age ballpark) birth date that can’t be traced?

What do you think of this theory?

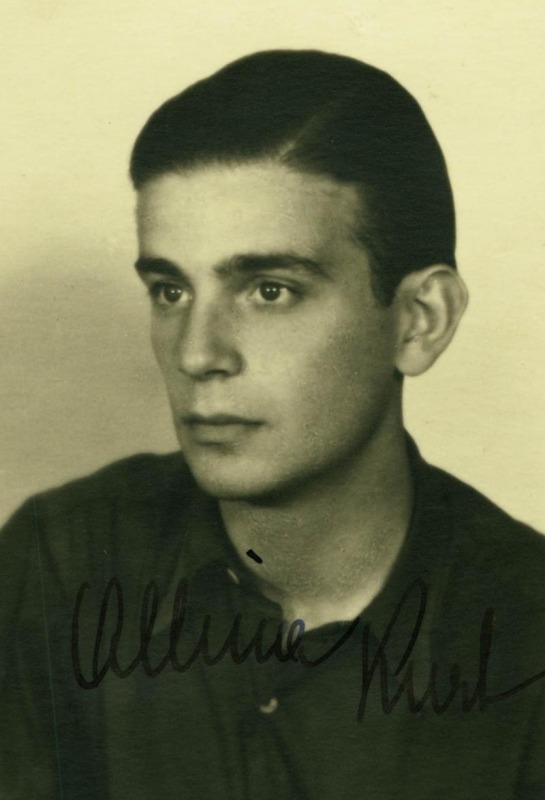

Note: The picture next to the title is of Curtis Allina, Erika’s brother. Sadly, I don’t have one of Erika.

Love the oddity of mixed numbers! My disclaimer on many posts on my family history blog is “Genealogy is a work in progress.” I hate being proven wrong in most of my life, but in this research, I really LIKE being corrected.

That’s why a genealogy blog, which you can constantly revise, is a better forum for this type of research than a book. That’s my story, anyway, and I’m sticking to it!

Do you know about fate Kamill and Jaroslav Allina?

I added Kamill’s wedding to the geni and some other information.

Martin

Hi Martin,

I’m afraid I don’t know what happened to Kamilla and Jaroslav Allina. I will look for your information on Geni — thanks!